The use of ice in art is a symbolic choice that effectively conveys its affordances as a literal and figurative representation of material transformation. In the examples discussed within this piece, it is evident that the temporary and impermanent condition of ice is consciously chosen by the artist(s). Its malleable and ephemeral qualities are the impetus behind the artful expression of themes that include economic, environmental, social justice and spiritual concerns. To paraphrase a line from rapper Vanilla Ice, “Stop, collaborate and listen,” making art with ice leads to a range of new intentions.

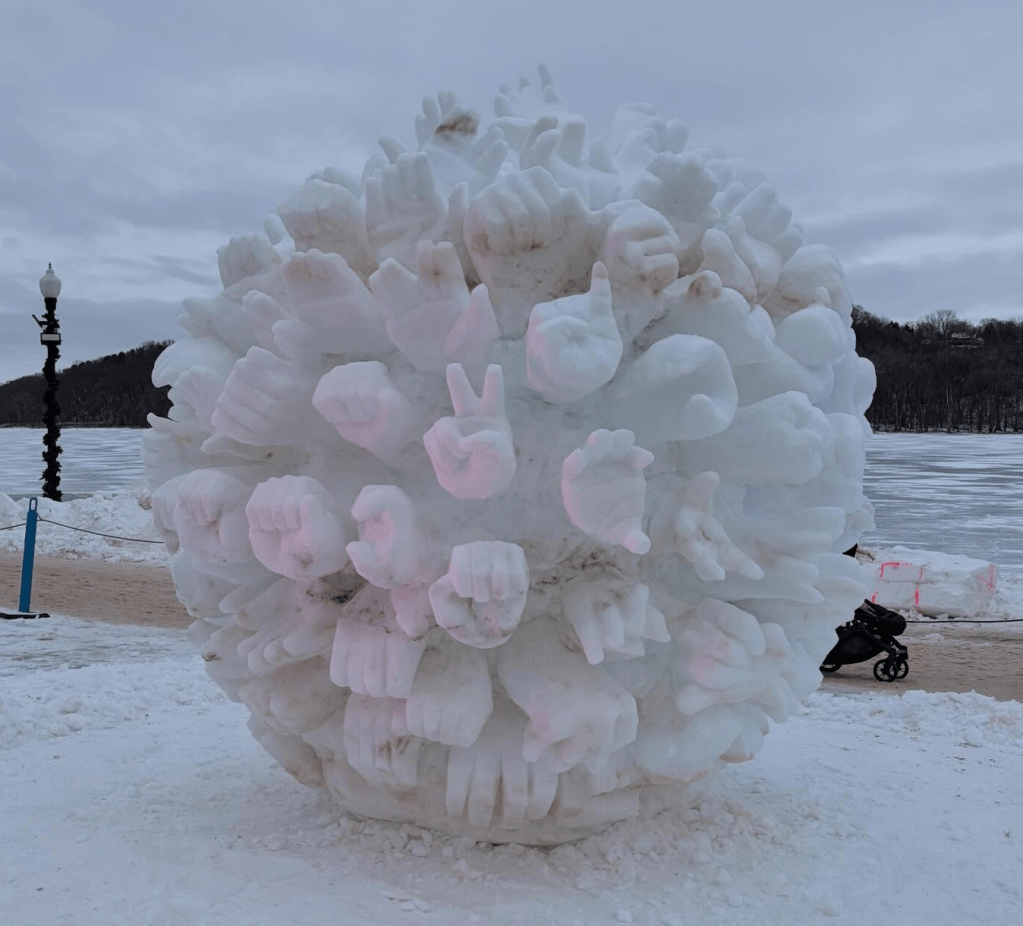

A Call to Arms (2026)

A Call to Arms was created by Team USA for the 2026 World Snow Sculpting Championship. It was a massive, larger than life-size snowball full of outstretched hands that symbolize peace signs, and communicate words in American Sign Language (ASL), including the messages “ICE out,” “love,” “unity” and “resist.”

The work was created by a team of artists under the moniker House of Thune, led by Minnesota-based Dusty Thune, who is both a seasoned ice-sculpting artist and special-education teacher for St. Paul Public Schools.

Unfortunately, the empathetic and poignant expressions within the artwork stirred controversy, leading to the sculpture’s removal from the competition. The organizers of the event stated that it was too politically motivated and even used the word “divisive.”

Thune astutely responded to the censorship of the sculpture, and is quoted in the Pioneer Press stating, “It seems that A Call to Arms did exactly what its description suggested: It opened an avenue for our voices to be heard, as well as for the voices of those that can no longer speak out to be remembered.” He adds, “‘ICE out’ isn’t a political message anymore. It is a humanitarian call for help.”

Thune’s statement highlights the fundamental value that art provides, which is a humanitarian form of communication and connectivity. Art is informed by the cultural context of its creation and interpretation, and has been a time-honored avenue for social commentary and systemic critiques. Even when not overtly activist-driven, the crux of art is an expression of human values, social structures and an insightful questioning of ethics.

The Sound of Ice Melting (1970)

In 1970, conceptual artist Paul Kos arranged eight boom microphones in a circle around twenty-five pound blocks of ice sitting in metal pans, which amplified the sound of the ice melting over a period of time. This symphony of natural phenomena was inspired by a Zen Buddhist koan, which is a paradoxical riddle that asks what the sound of one hand clapping sounds like.

The riddle is conveyed through the narrative of an interaction between a Zen master named Mokurai and a twelve year old student named Toyo who wishes to study under the master. The master considered Toyo to be too undisciplined initially, so he gives the prospective student an inquiry to ponder: “You can hear the sound of two hands when they clap together,” said Mokurai. “Now show me the sound of one hand.” Upon contemplating the question back in his room, Toyo heard various sounds, such as the singing of geishas, the dripping of water and the whistling of wind, but each time he came back to Mokurai, he was refused. Those were not the sounds of one hand clapping. Finally after an extensive period of time going back and forth and contemplating whether various ambient sounds could be the answer, Toyo realized that he could collect no more, and reached the soundless sound, which was intended answer that Mokurai sought from his young student.

The koan is absurd in its premise, because one hand alone cannot produce a clapping sound. The point of the exercise is to elicit a mindful method of contemplation that enables practitioners to liberate themselves from intellectual understanding and undertake a direct, experiential awareness of themselves and their surroundings.

The Sound of Ice Melting resembles the way a press conference is often set up, but the subject is not a politico emphatically posturing to an audience. Ice does not convey pithy messages, but what it can communicate to us is a sense of personal and collective realization regarding our place and relationship in the natural world. The sounds of natural transformation are not always audible, but they are continually happening whether we are cognizant of it or not. Kos’ work does not specifically speak to climate change, but it is hard not to reflect upon the work in relationship to the Anthropocene.

I experienced The Sound of Ice Melting when it was recreated (as it has been several times) for the exhibition The Third Mind: American Artists Contemplate Asia, 1860–1989 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim museum in 2009; and despite making a connection to environmentalist themes, my sensory response to the installation was more personally reflective than anything else. I stood in the museum lobby for several minutes, initially listening very intently to the methodical sound of ice melting. It was hard to miss because the dripping and cracking was amplified loudly from both the microphone arrangement and the architectural acoustics of the building’s grand marble rotunda. The sounds became indistinguishable from the other types of ambient noise such as museum visitors footsteps and chatter; and I realized that there was a profound distortion of the natural world due to our frenzied and materialist driven lifestyle. Eventually, the conscious listening transpired to a subconscious state of mind and I practically heard only the thoughts inside my own head. I was composing electroacoustic music at the time, and left the exhibition full of new tonal and sonic possibilities.

Paradox of Praxis I (Sometimes Making Something Leads to Nothing) (1997)

When working with ephemeral materials like ice, time is a major factor in how the work gets implemented, presented and consumed. Francis Alÿs spent nine hours engaging with a big block of ice, which he pushed around Mexico City as it steadily melted. Paradox of Praxis I is both whimsical and critical of the relationship between the human and environmental process of creating. As Alÿs moves the ice throughout the city the block becomes less cumbersome. Initially he had to push it with two hands, but by the end of the journey he was simply kicking it with one foot.

This can be a metaphor for labor, both from an artistic and general perspective. The exploitation of labor is reflected in the arduous task of moving a large block of ice throughout the city, only to be left with a puddle at the end. Laborers are asked to spend the better part of their days and lives toiling on projects in which their compensation is minuscule in comparison to the highly profitable corporations and rich bosses they are working for.

In a digital and materialist culture, we take creative processes for granted. We crave the end product for consumption, but have little desire to engage with the tedious and concentrated labor behind the scenes. In terms of cultural capital, the product is where value is placed, and it is often powerful economic forces (i.e. a corporation, gallery or production company) that profit the most without having to do extraneous toiling. Alÿs’ own marathon endeavor was edited down to just a few minutes of footage, since it is likely that very few people would willingly spend the time watching all nine hours of it. That aspect in and of itself signifies the intention behind the artwork’s title.

Ice Watch (2014)

In 2014, artist Olafur Eliasson and geologist Minik Rosing fished out large floating blocks of ice from the Nuup Kangerlua fjord in Greenland. The chunks of broken ice were once a part of Greenland’s ~1.7 million ice sheet that covers eighty percent of the massive arctic island. Greenland’s ice sheet has been melting at an accelerated rate since 1998, making it a major benchmark for tracking and studying the Earth’s climate change.

The artist/scientist duo initially installed the ice blocks in Copenhagen’s City Hall Square during the United Nation IPCC’s fifth Assessment Report on Climate Change in October 2014, where the public could interact with the ice and witness the effects of climate change in person. The work has been replicated several times in different public spaces, such as in front of the Tate museum in London in 2018.

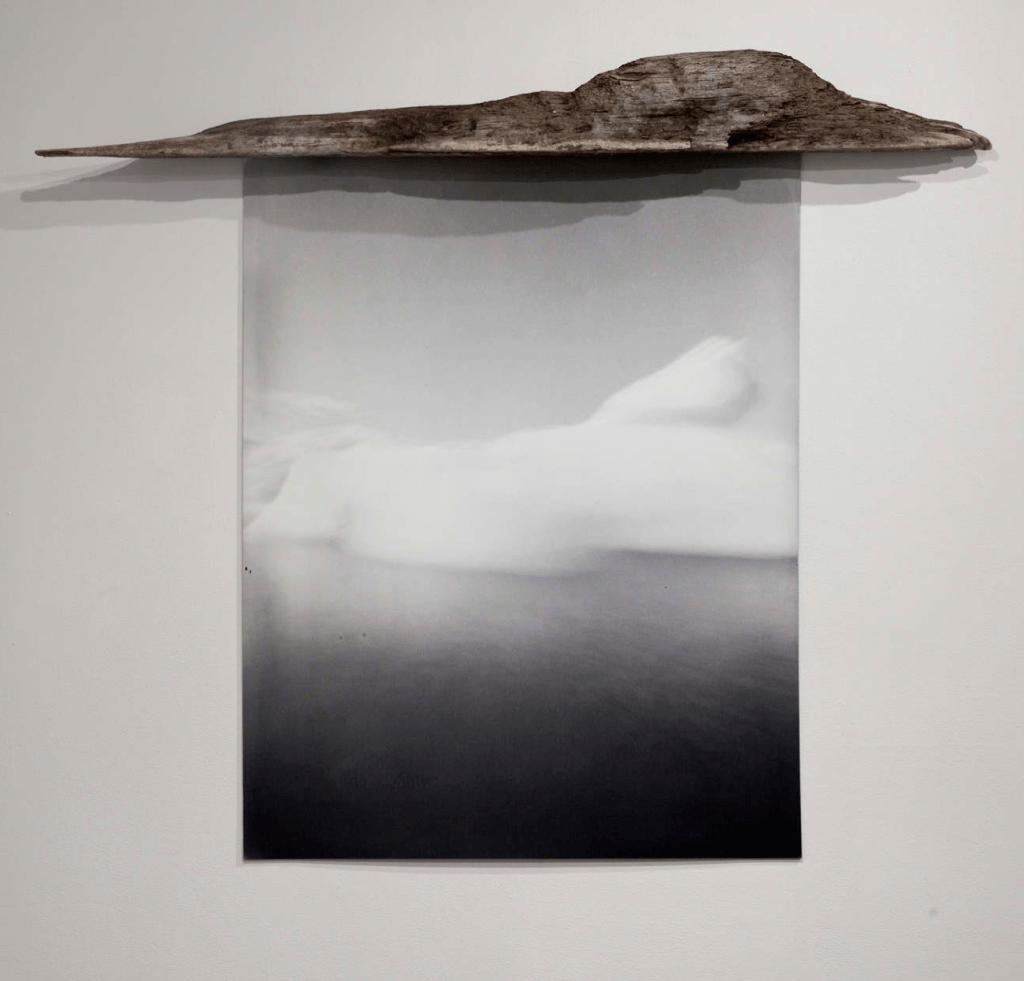

Arctic, Future Relics (2014)

In the summer of 2014, artist Vanessa Albury traveled on a Barkentine sailboat around Svalbard, Norway and the Arctic Ocean, where she took day trips to observe and capture the imagery of glacial ice caps in the Arctic Circle using a pinhole camera. The result of her exploration is a series of mixed-media work called Arctic, Future Relics. Ghostly in composition, these photographs, which also incorporate pieces of Canadian driftwood as support beams, capture the majestic ecological forms undergoing a process of decay. The series not only documents the degradation of the polar ice caps, it serves as a poignant memorial for what is being lost due to climate change.

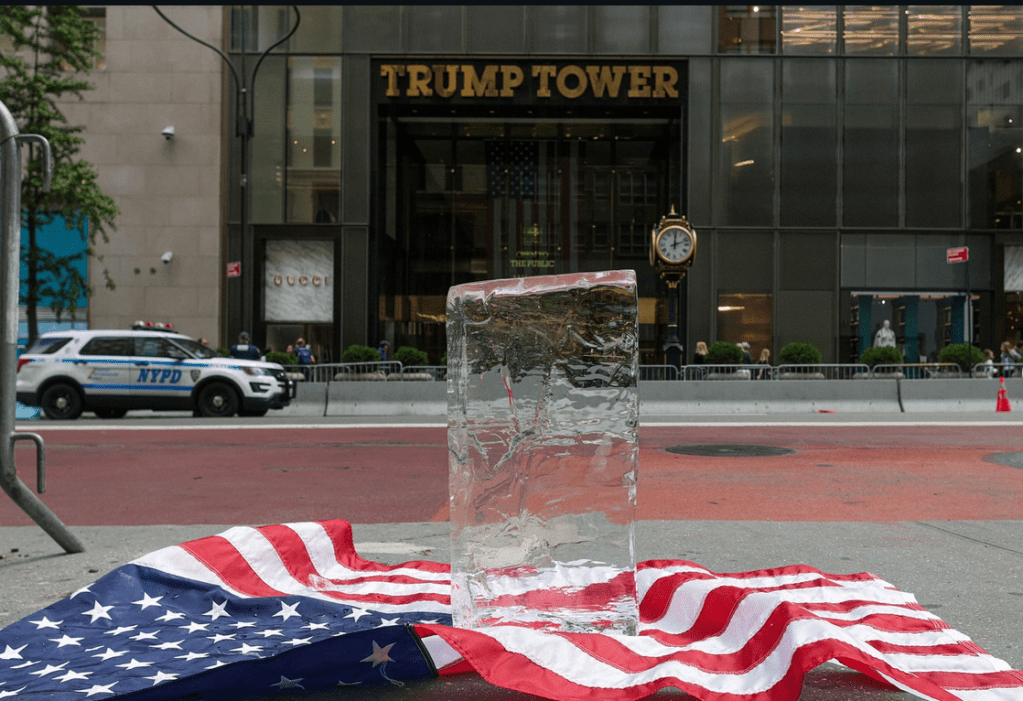

Executive Order 14341 (2025)

“He requested the flag not be burnt….nothing was said about freezing it,” exclaimed artist Perry Picasshoe, describing their motivation behind the creation of Executive Order 14341. Picasshoe placed a seventy-five pound block of ice on top of an American flag, which was laid upside down on the sidewalk across from Trump Tower in Manhattan. The aforementioned quote is in regard to an executive order that Donald Trump signed in 2025, which prosecutes the act of burning the flag, a form of political protest that is protected by the First Amendment.

Picasshoe’s account of the performative installation is as follows: “People gathered and took smiling pictures next to this ice block and the Trump Tower sign. (I wonder to what extent they knew what they were doing?) A small crowd began to gather, enough for the police standing guard across the street to take notice. No more than five minutes later, the police rushed over to remove the flag and toss the ice block on its side. The flag was taken while the block of ice remained. For the next eight hours, the ice remained and eventually slid down onto the gutter where it laid there to melt away.”

Executive Order 14341 encapsulates art’s fundamental value and enduring role in creating vibrant forms of expression that are essential for cultural progress, societal critique and personal and collective liberty.

Discover more from Artfully Learning

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.