This piece is a slight reworking and expansion of previously published posts on my Artfully Exercising platform.

Barbara Lubliner is a visual and performance artist who goes by the moniker Ms. Muscle. As an artist she flexes her creative muscles to pay homage to the strength and prowess of women. She also flexes her actual muscles, revealing a pair of sculpted breasts on top of her biceps.

Ms. Muscle’s persona is an amalgamation of symbolic iconography. The aforementioned breast biceps, a long sheath gown, tiara and a pageant sash that reads “Ms. Muscle,” express beauty, brains and brawn through a feminist lens.

By means of public performances and interventions, Ms. Muscle emphasizes strong women from the past and present. In celebration of Women’s History Month, she led a six mile walk across the island of Manhattan to visit monuments depicting historical women (Gertrude Stein, Golda Meir, Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Harriet Tubman).

Lubliner has also posed, muscles flexed, alongside paintings by women artists. In a series of performative photographs, called Making Their Mark, Ms. Muscle juxtaposes herself among paintings, sculpture and installation art by modern and contemporary artists including Joan Mitchell, Howardena Pindell, Tschabalala Self and Simone Leigh.

Additionally, Ms. Muscle provides a platform for women to participate in her art. She’s led singalongs of Helen Reddy’s feminist anthem, I am Woman (1972):

I am woman, hear me roar

In numbers too big to ignore

And I know too much to go back an’ pretend

‘Cause I’ve heard it all before

And I’ve been down there on the floor

And no one’s ever gonna keep me down again

In her participatory performance, Roar with Ms. Muscle, she walked along 14th Street in Manhattan, approaching women of all ages who join her in a sing along of the song’s first line.

Lubliner explains that the focus was on “ROARING and channeling ‘Hulk-like’ energy for what participants wanted to proclaim.”

Throughout modern United States history, allegorical figures like Rosie the Riveter, an artistic rendering of a factory worker, have stood as symbols for women’s independence and equality across culture. Rosie became a feminist icon by rolling up her sleeves, flexing her biceps and exclaiming, “We Can Do It!” As is Ms. Muscle, who prompts us to consider the various meanings and representations of feminine strength. In her words, she “wants to empower everyone to be their Biggest and Breast self!”

Muscles are too frequently a point of contention when discussing women’s physiques, due to a prejudiced male gaze and chauvinistic ideologies. The objectification of women’s appearance has influenced how women’s bodies are idealized in mass media, art and athletics (to name a few disciplines where women’s bodies are heavily scrutinized and controlled by public opinion). In his 1972 book, Ways of Seeing, art critic, John Berger wrote, “Men survey women before treating them. Consequently how a woman appears to a man can determine how she will be treated.”

While muscles are often associated with athleticism for men, female athletes have been ridiculed if they are perceived as “too muscular,” and are subjected to public bias and smear campaigns due to their physique. The arts have addressed these issues to various degrees with depictions and expressions of swole women.

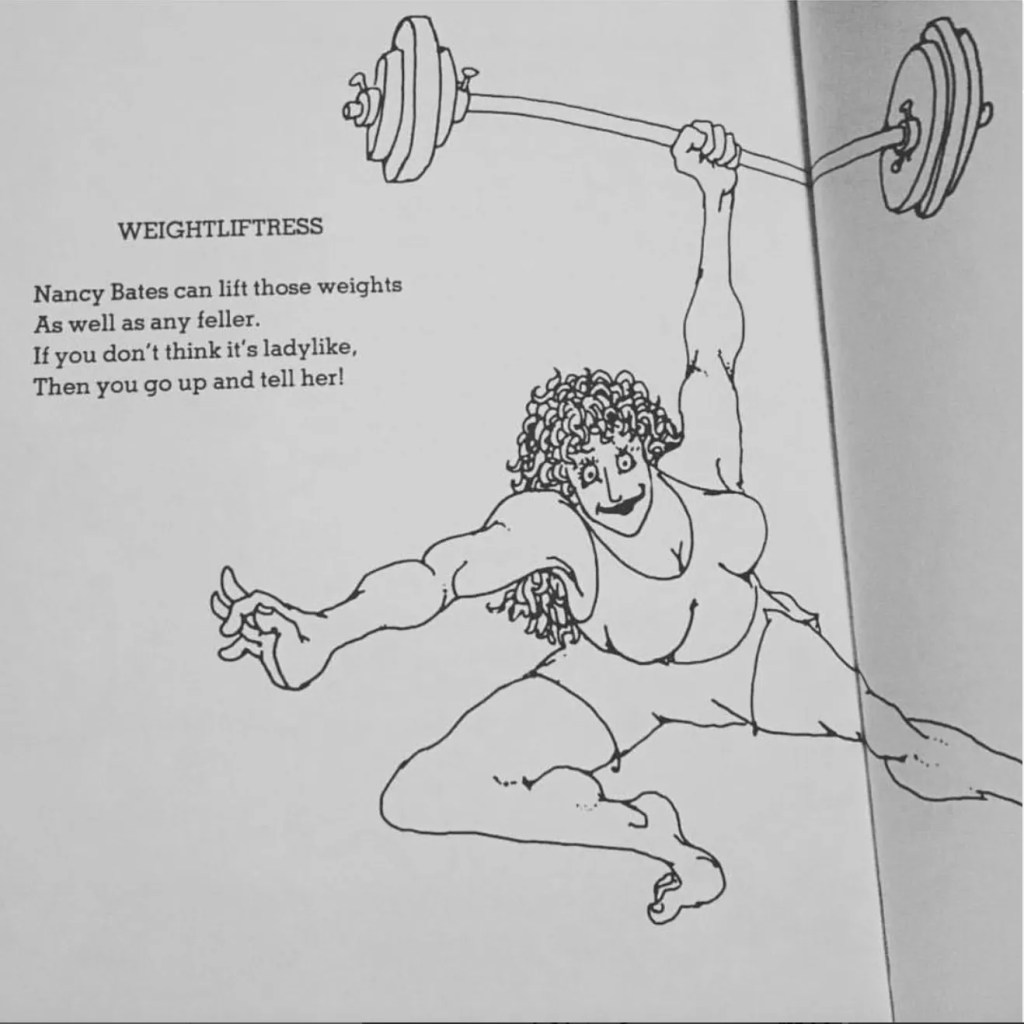

Shel Silverstein, the late poet and musician who utilized poetry and song to express his cultural observations, wrote a poem titled Weightliftress (1974); eschewing the social construction of femininity and masculinity in a fitness context, with an ode to a fictional female bodybuilder named Nancy Bates. In four lines, the poem challenges stereotypes about strength that exist due to the cultural influence of the male gaze and masculine hegemony. It should be noted that Silverstein’s style of art is not feminist in nature, and he has indeed contributed to the male gaze via illustrations for Playboy magazine and other adult themed content. But his modus operandi is satire, and Weightliftress and other poems and works by Silverstein that examine the role of gender (such as The Giving Tree, a work that has been critiqued as ‘sexist’ for upholding masculine and feminine domestic tropes; a topic better served for a post all on its own) have an acerbic tone regarding gender inequality. Perhaps, Silverstein was being self-reflective, realizing his own role in the patriarchy and how he has benefited from it. However the narrative(s) of his work is explored, it clearly has potential to prompt critical discussions around gender identity.

A similar issue arises with the portrayal of She-Hulk, a fictionalized literary character created by Marvel Comics in 1979 as a counterbalance to the Hulk. Her real identity is Jennifer Walters, and she is an attorney who got her superhuman powers through a blood transfusion from her cousin, Bruce Banner, aka the Hulk. Rather than assuming the full frontal brutishness of the Hulk, She-Hulk’s transformation is milder. Whereas Banner’s Hulk is a raging ball of unmitigated testosterone, Walters’ is able to maintain her social and emotional intelligence alongside her newfound She-Hulk persona. As such, She-Hulk is both a figure of feminism as well as a victim of chauvinism. She is typecast as a gentler, more “feminine” (if you will), Hulk. Her strength and self control gives her assuredness, but also is stifling. Being compared and contrasted to her male counterpart makes She-Hulk a more conventional figure within gender studies. Furthermore, her physique has been designed and developed through the lens of male comic book artists; and although her look has changed throughout the years, there has always been a parallel to fashion models and Golden Age women bodybuilders.

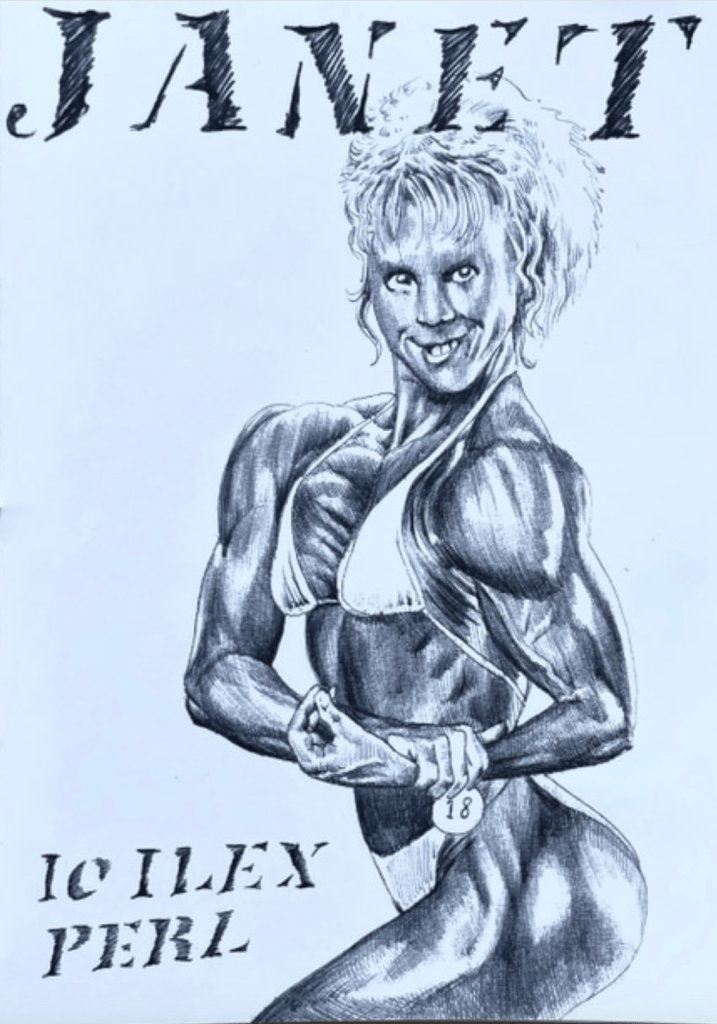

Whereas She-Hulk and Nancy Gates are figments of male imagination, artist io ilex perl’s zine titled Janet, contains drawings of an actual professional female bodybuilder from the 1980s, named Janet Kaufman. The suite of drawings are nearly identical, varying slightly in tone; and reveal a layered approach to adding detail through a repetitive and cumulative process that signifies the formulaic nature of training to become a bodybuilder. Perl’s attention to detail results in a very analytical representation of Kaufman’s muscles, joints and ligaments in a state of contraction. Janet is assertive and strong, and eschews the male gaze with a heterogeneous display of femininity.

These examples each bring to light the wide connection between physical education and the arts, and the importance of considering both discipline’s relationship towards upholding, challenging and transforming conventions of body image and gender. The reality of human nature is that displays of strength are not adherent to the confines of gender. To paraphrase the words of Rosie the Riveter, “We can all do it!”

Discover more from Artfully Learning

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Love 💪🏼

LikeLiked by 2 people