With the blockbuster live action Barbie movie premiering soon, I thought it would be timely to discuss how the iconic fashion doll, and the sociocultural ideals it represents has been examined through works of art. In this instance, I have chosen to focus on works by contemporary artists Adrian Piper and Chantal Feitosa.

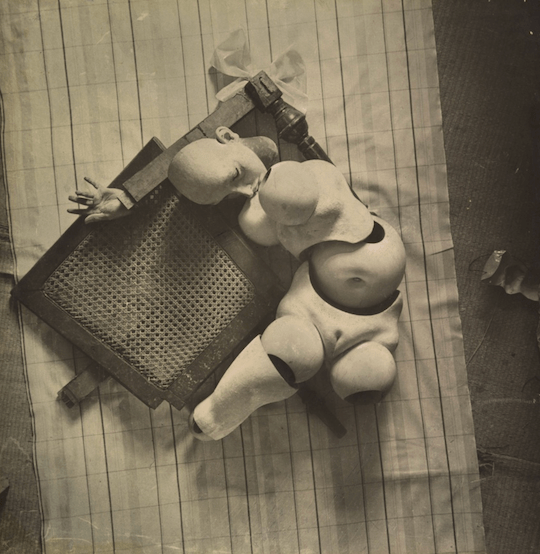

Dolls were a fascination of Surrealist artists such as Hans Bellmer, who is best known for his photographic work involving manipulated doll compositions made in Germany between 1933 and 1938. Bellmer’s doll imagery has a complex legacy, in that it is both lauded (see: Bell, 2014) and loathed (see: Gauthier, 1971 and Kuenzli, 1990) by feminist scholars. His dolls are the antithesis of the ideal forms and features that make playing with dolls a fun and childlike endeavor. By mangling and deforming the appendages, Bellmer’s dolls are symbolic of how bodies are fetishsized and subjected to violence and exploitation. Indeed, Bellmer was responding to both his own taboo sexual desires, as well as his being witness to the violent acts of corporeal dehumanization carried out by the Nazis. Therefore, the dolls were a personal means for Bellmer to come to terms with several perverse and confounding notions. Art curator and critic Michael Duncan (1993) notes, they are reflective of “a complex nexus of desires: as a throwback to the fantasy life of his childhood, as a way to shock his bourgeois Nazi father, as a cathartic surrogate for his desire for young girls and as an expression of his love for his ailing wife, Margarete.”

Just as art and life mirror one another, dolls reflect our overarching cultural attitude and perception of identity. In the 1940s psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark sought to prove their hypothesis that children’s development of racial bias has roots in a material culture that is largely geared towards the perspectives and disposition of white hegemony. The duo carried out an experiment using dolls, which revealed that Black children were conditioned to assign negative traits towards their own race and social status. When the Clarks presented African-American children with a Black doll and a white doll and asked them which doll they preferred, the children overwhelmingly chose the white doll. Furthermore, they attributed more positive attributes (i.e. blonde hair and blue eyes) to the white doll than to the Black doll. The study reflects how segregation and racial stereotypes have a significant impact on a child’s social, emotional and cognitive development, and does enormous damage to their self-esteem. The results of the doll tests were pivotal in deciding the Brown vs. Board of Education case, which ruled that racial segregation in schools was unconstitutional (Blakemore, 2018).

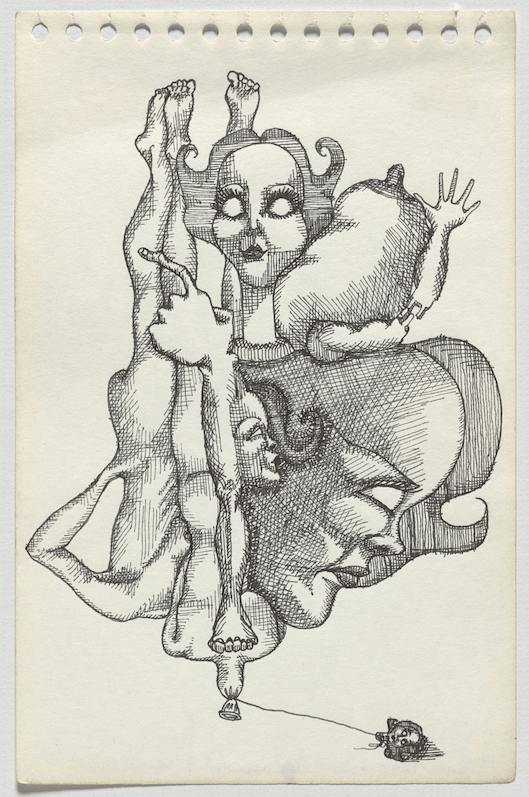

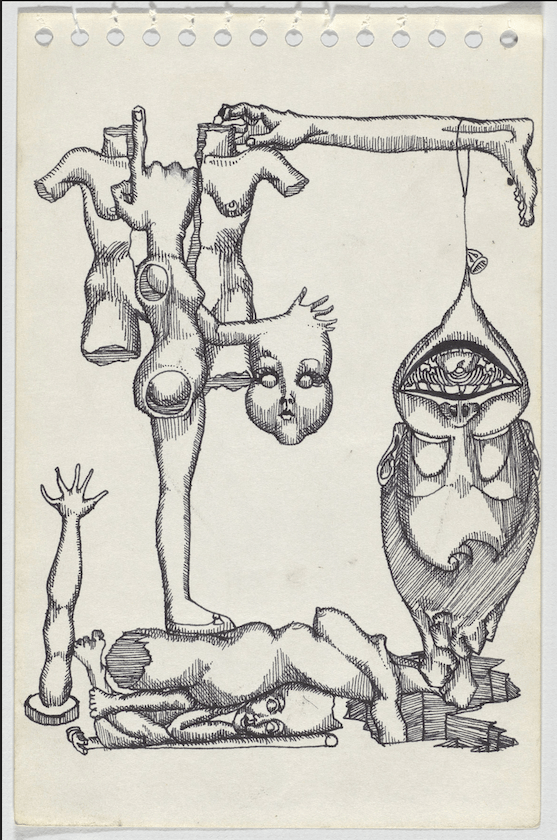

Both Bellmer’s surreal constructs and the Clark’s doll experiment are relevant to the poignancy of Adrian Piper’s Barbie doll drawings. Piper created these drawings in 1967 when she was around eighteen or nineteen years old. Through these pencil and ink drawings Piper addresses Barbie’s iconic status as a barometer for determining ideal perceptions of body image during childhood. Several studies have identified that playing with Barbie dolls, which are usually incredibly thin, voluptuous and lacking in ethnic diversity, can lead to self-deprecating thoughts and behaviors in young children that have long term psychological and physiological impact (see: Engeln, 2021). Fifty years after the Clark doll experiment, a study of Barbie dolls conducted by Mattel, the dolls’ manufacturer, had similar results: non-white children preferred playing with the idealistic and archetypal white dolls to more ethnic dolls (Colucci, 2018).

Piper’s drawings hearken back to the Surrealist game of “Exquisite Corpse” where participants blindly contribute a piece of anatomy to a drawing of a figure. The figure often becomes more absurd with each player’s addition. The dolls which Piper based the compositions on have been broken down and reconstructed so that they are anatomically incorrect with exaggerated features. Cultural critic Emily Colucci (2018) aptly notes that “Piper rearranged and reconfigured her parts, turning her into the monstrous creation she always was.”

Chantal Feitosa’s Happy Mulattos: Collector’s Edition (2018) is both a participatory artwork and a profound sociological study that reinforces how racial stereotypes can be upheld by material culture and childhood play. Feitosa handcrafted a group of dolls with features representative of mixed-race individuals (a Mulatto is a derogatory term that has been used to describe a person of mixed white and black ancestry), which were then introduced to ‘focus groups’ of nursery school-aged children through a series of organized ‘playdates’ (Happy Multattos: Playdates, 2018). The children’s responses to each doll’s physical features expressed playful ingenuity, but also showed that at their early stages of social and cognitive development, they had already established specific notions about race, gender and beauty standards.

Piper’s 1981 drawing Self-Portrait Exaggerating My Negroid Features and Feitosa’s American Dream Girls performance (2018) extends their critique on body image and the male, colonial gaze that often prevails in art and entertainment circles.

Piper’s bi-racial self-portrait confronts us to apply our own biases by considering what features she is referencing in the title. It is a playful, yet poignant exercise in racial profiling. By highlighting features that are atypical of Western art, Piper eschews the Eurocentric conventions of beauty and desire that are commonly associated with art historical portrayals of women.

In American Dream Girls Feitosa wears handmade terracotta masks and poses in nature to embody namoradeiras figures, which are popular Brazilian home decorations that are typically affixed to windows or balconies. These figures are said to represent girls who are awaiting their “sweethearts.” Transferred to the cold and wooded landscape of Colorado, Feitosa detaches the namoradeira from her traditionally static and subservient position and into the vast American wilderness where she might be subjected to fetishization by Western pioneers. Feitosa explains that, “through the embodiment of the namoradeira, I was interested in staging gestures of longing and desire that are both highly visible yet difficult to access and interpret. This body of work has also begun to touch upon my interests in alienation, escapism and the myth of Western ‘discovery’ at the expense of the colonized body across time and continental borders.”

Judging from the rather vague synopsis and trailer, it is possible that the upcoming Barbie film might seek to address (albeit in the jejune way Hollywood attempts social awareness) some of the aforementioned issues of unrealistic and explorative body image. The premise I have gathered is that Barbie and her counterpart Ken are expelled from Barbie Land, a utopian alternate universe, for being “less-than-perfect dolls.” As a result, they embark on a journey of self-discovery within the real world. Will the film do enough to make an impact on the mainstream audience’s social consciousness? Time will soon tell, but I am hopeful that a mainstream movie can provide transformative impact on how we discuss body image and identity. We are in dire need of a paradigm shift that centers the identities and experiences of intersectional feminism instead of the time-honored white feminist arc that has shaped the narrative of material culture and entertainment.

References, Notes, Suggested Reading:

Bell, Jeremy. “Uncanny Erotics: on Hans Bellmer’s Souvenirs of the Doll,” Feral Feminisms, Issue 2, 2014. https://feralfeminisms.com/uncanny-erotics/

Blakemore, Erin. “How Dolls Helped Win Brown vs. Board of Education.” History. 27 March 2018. https://www.history.com/news/brown-v-board-of-education-doll-experiment

Colucci, Emily, “Why Is Everyone Sleeping On Adrian Piper’s Teenage Doll Paintings?” Filthy Dreams, 10 May 2018. https://filthydreams.org/2018/05/10/why-is-everyone-sleeping-on-adrian-pipers-teenage-doll-paintings/

Duncan, Michael. “Hans Bellmer,” Frieze, 5 June 1993. https://www.frieze.com/article/hans-bellmer

Engeln, Renee. “Barbies May Do Damage That Realistic Dolls Can’t Undo,” Psychology Today, 23 March 2021. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/beauty-sick/202103/barbies-may-do-damage-realistic-dolls-cant-undo

Gauthier, Xavière. 1971. Surréalisme et sexualité. Paris: Éditions Gallimard.

Kuenzli, Rudolf. E., (1990) “Surrealism and Misogyny”, Dada/Surrealism 18(1), 17-26. https://pubs.lib.uiowa.edu/dadasur/article/id/29424/

Discover more from Artfully Learning

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.