Astronomy is the study of how the universe was formed, and the objects such as planets, galaxies and stars within it. It is a major part of the science profession, and a fundamental part of the science curriculum from kindergarten through high school. An astronomy curriculum incorporates many interdisciplinary elements such as engineering, math, chemistry and physics. While the aforementioned aspects are reliant on computational and quantitative data, studying astronomy also necessitates making detailed models and renderings of objects that are observed throughout the universe. This latter facet is where art has been integral in advancing the field of astronomy, and is a big reason why the heavy focus on STEM education (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) should rightfully be upgraded to STEAM.

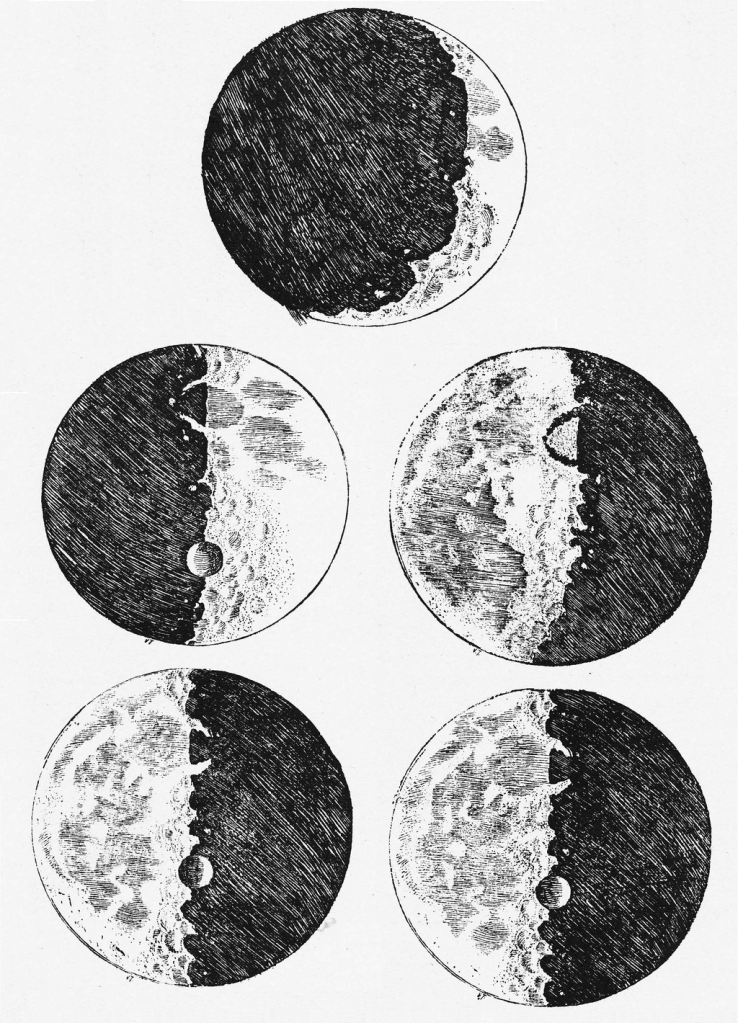

Seventeenth century Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer Galileo Galilei (known simply as Galileo), is widely considered to be the leading figure in the canon of observational astronomy (meaning the practice and study of observing celestial objects using telescopes and other instruments, as well as the naked eye). In 1610, Galileo published Sidereus Nuncius, an informative text that contained sketches he made while looking through his telescope. Objects that were rendered in ink, graphite and watercolor include detailed depictions of the moon’s lunar surface, which represents a tangible and accurate visualization of the moon’s characteristics hundreds of years before photographs and physical exploration. While his contributions to the advancement of scientific discovery are well known, Galileo’s aesthetic insight was invigorating and revelatory for its time and place as well.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Science writer Mara Johnson-Groh (2019) elaborates on the artistic elements in Galileo’s astronomical recordings, noting that he: “drew on art techniques like perspective and chiaroscuro — a manner of depicting light and shadows that was relatively new at the time — to show the lofty mountains and craters on the moon’s imperfect surface. Using geometry and his drawings as a measuring stick, he was even able to measure their heights with astonishing precision. Two years later, Lodovico Cardi, also known as Cigoli, a prominent Florentine painter, immortalized Galileo’s sketches of the moon in a fresco that still stands in the Santa Maria Maggiore, a Basilica in Rome.”

Of course no one person can truly lay claim to being the first to observe, analyze and interpret objects in the sky. There are prime examples of visual objects dating back as far as the prehistoric era suggesting that the culture and personas of our early human ancestors were inspired by celestial phenomena (see: Imster, 2018). Astronomical exploration, discoveries and insight were being developed outside of the European continent simultaneous with Galileo’s work. For centuries and into the present day, cultures throughout the world have made formative distinctions about the universe and celestial objects. These cultures established and passed down detailed records of the celestial objects they observed. Their documentation shows an understanding of the alignment and movement of planets and stars over fixed periods of time. These enduring understandings are integral to their culture at large and have beneficial impacts that have enabled communities to prepare for annual occurrences and navigate the natural environment. In Australia, Indigenous astronomy is part of the National Curriculum.

Recognizing different perspectives and insights derived from astronomical observations provides a far more detailed map of the universe and our relationship to the cosmos than any canonical study could. This overarching study of astronomy is made more replete through the significant strides and contributions the arts have made within the STEM fields. Art enables us to make connections between the applied sciences and the various conditions of humanity. Art’s elaborate visual vocabulary has led to an inspiring range of emotional and experiential narratives related to the study of theoretical and observational astronomy. Nearly every single past and present culture has created their own traditional context for understanding the cosmos, which combines tangible observation and reasoning with artful storytelling or symbolic depictions.

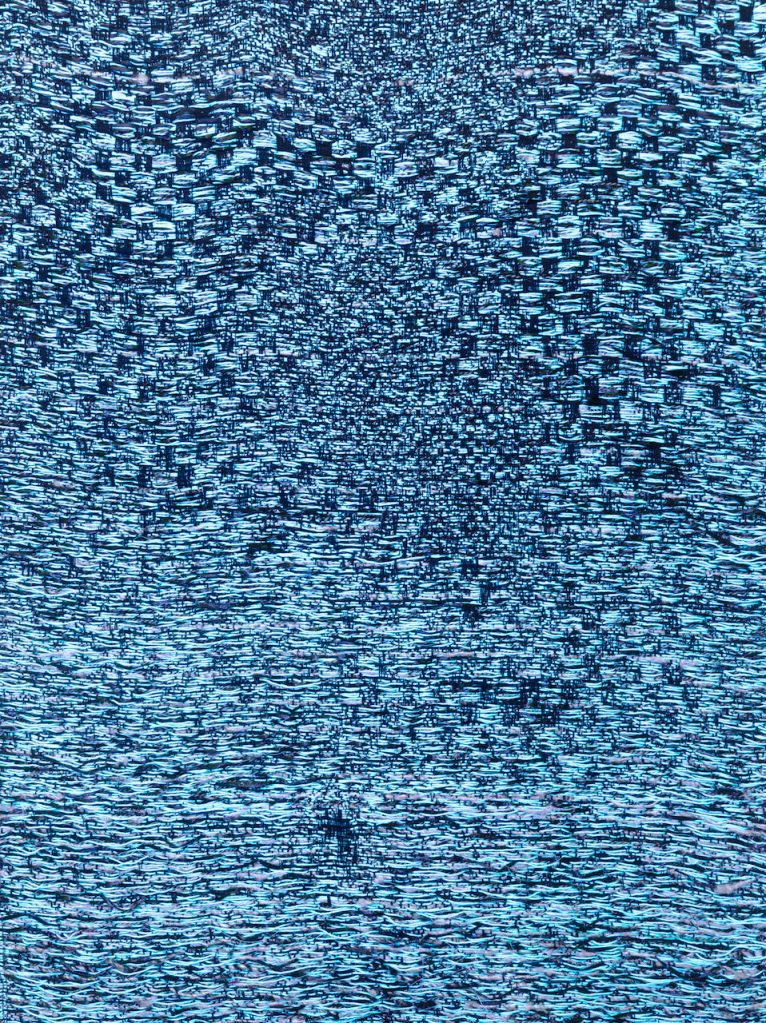

Photo by Ian Byers-Gamber.

Sarah Rosalena‘s exhibition and series of artworks titled Standard Candle, challenges the traditional tropes and understanding within the field of astronomy by re-presenting astronomical observatory instrumentation through feminist and anti-colonial perspectives. The process behind the exhibition (on view at the Mount Wilson Observatory in Los Angeles, California through June 18, 2023) is a symbolic response to the scientific elements of Native craft traditions, and the labor of female ‘computers’—women who worked at observatories undertaking the painstaking tasks of graphing data and performing calculations and predictions using glass plate photographic images.

The title of Rosalena’s project references the astronomical practice of measuring the rungs on what is known as a “cosmic distance ladder” to determine the size, age and expansion rate of our universe via the known luminosity of celestial objects. NASA explains that: “the ladder’s first rung consists of pulsating stars called Cepheid variables, or Cepheids for short. Measurements of the distances to these stars from Earth are critical in making precise measurements of even more distant objects. Each rung on the ladder depends on the previous one, so without accurate Cepheid measurements, the whole cosmic distance ladder would come unhinged.”

Rosalena’s interdisciplinary body of work merges digital and Indigenous weaving processes to reinterpret telescopic images as woven and beaded textiles. The stylistic motifs on these artworks are based on glass plate imagery used in the early nineteenth century by women data scientists working at the Mount Wilson Observatory to map the universe by generating units of measurements through a grid system.

Rosalena’s process included creating handwoven textiles on a digital Jacquard loom using computer coding; and making glass beaded textiles on her mother’s Wixárika handloom using Indigenous weaving techniques that were passed down from her matrilineal bloodline. This endeavor speaks to the ways many Indigenous cultures integrate complex belief systems into tangible scientific observations, as well as the integral role that women have had in technological advancement throughout the course of human history (see: the Women Interwoven documentary series for many different examples). In this manner, the term standard candle is made more expansive and inclusive of non-traditional hierarchies within the field of science, computing and space exploration. She notes that “I often thought of my grandmother who has passed on, and had multiple dreams about her. Also, thinking about my body as an inherited algorithm. I believe she has been weaving with me in the process of the work” (Rosalena, 2023). Creating all the artworks for the exhibition was incredibly labor intensive, totaling over 300 hours of work. This reflects the diligent work of the women who made significant contributions to the field of astronomy, but are often unsung in its canonical narrative. Rosalena explains that their groundbreaking efforts to advance modern astronomy represents “this whole genre of history where people [were] just being completely erased. And we forget all the labor that goes into our computers” (quoted in Guilhem, 2023).

Rosalena’s art-centered rethinking and re-presenting of scientific discovery and its key contributors, is also a sentiment within Annette S. Lee’s practice. Lee is both an artist and astronomer. She merges the two disciplines to communicate how Indigenous astronomy is directly connected to the human experience and is intrinsic to the identity of Indigenous communities. In many Indigenous cultures, life itself originates in the stars. They are homes of ancestors, flora, fauna and other spiritual beings. They measure time, which forms the basis of traditional events, sociocultural benchmarks and quotidian moments in daily life. In this sense, the stars are part of their genetic code, as well as their code of conduct. Science utilizes the aforementioned social and cultural systems, as well as data and formula driven coding.

Courtesy of the artist.

Lee’s artwork speaks to this distinctly human aspect, as well as the more computational elements of astronomy, by merging the conventions of STEM related disciplines with Indigenous science. Her “Generative Art” series attempts to make these seemingly divergent facets coalesce in a complimentary manner. With titles such as Summer Kapemni – Star Relatives, Plant Relatives – Pilamayaye, Miigwech”, Thank you for Life (2022), these digitally rendered artworks speak to the universality of traditional Lakota concepts like Kapemni, as well as Cloud computing.

Kapemni is a Lakota word that means “as it is above; it is below,” and signifies the relationship of the sky and Earth as a repository for life and creative endeavors. The Cloud is a means to network vast and differentiated content created digitally so that it can be stored and shared globally, and operate as a single ecosystem. We use the Cloud to experience digital culture in real-time and store things that are memorable and important. There have even been discussions of an “afterlife” within the Cloud (see: Hopkins, 2013). All of these characteristics are akin to how stars contain vast information about the universe and human cultural traditions. This exemplifies and visualizes Lee’s enduring understanding about science being inseparable from the arts and other imagination-driven disciplines. She rightfully asserts that “as much as there’s this idea that science is all rational, science is immune from culture, that’s simply not true. Science itself is not actually separate from culture” (quoted in Taylor, 2019).

References, Notes, Suggested Reading:

For more information on Indigenous astronomy including educational resources, head on over to Native Skywatchers, an Indigenous led organization founded by Annette S. Lee et al.

Guilhem, Matt. “‘Standard Candle’ focuses on space, scientific progress, women’s work,” KCRW, 17 May 2023. https://www.kcrw.com/news/shows/greater-la/renaissance-mt-wilson-andrea-zittel/standard-candle-sarah-rosalena

Imster, Eleanor. “Prehistoric cave art suggests ancient use of complex astronomy,” EarthSky, 6 December, 2018. https://earthsky.org/human-world/prehistoric-cave-art-suggests-ancient-use-complex-astronomy/

Hopkins, Jamie. “Afterlife in the Cloud: Managing a Digital Estate” 5 Hastings and Science Technology Law Journal, 210, 2013. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2248008Im

Johnson-Groh, Mara. “Sketching the Stars: How Art Can Advance Astronomy,” Undark, 3 June, 2019. https://undark.org/2019/06/03/astronomy-art/

Rosalena, Sarah. “Sarah Rosalena’s Standard Candle uncovers the forgotten history of female ‘computers'” Creative Capital, 2 May 2023. https://creative-capital.org/2023/05/02/sarah-rosalenas-standard-candle-uncovers-the-forgotten-history-of-female-computers/

Taylor, Christie. “Relearning The Star Stories Of Indigenous Peoples,” Science Friday, 6 September 2019. https://www.sciencefriday.com/articles/indigenous-peoples-astronomy/

Discover more from Artfully Learning

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

A most interesting and informative text, showing great art.

LikeLiked by 1 person