Learning is intrinsic to living, hence the term “lifelong learning.” Data from a 2020 study suggest that people typically have more than 6,000 thoughts per day (see: Raypol, 2022). This might seem like a vast and abstract number, but just think about how many different things cross your mind every day. All the choices you make, things you observe and the actions you take, contribute to this total. The only time that we are not processing information, or empirically learning, is arguably when we die. But even death is a part of life, and dying is not always a sudden act. Therefore, the process of death is tied in with the overall concept of lifelong learning. It is the final act of the experiential learning process, and one of the most conceptualized parts of the cycle of life.

Artists and artisans have explored death and dying throughout the course of recorded history. The most renowned example is the ancient Egyptian culture, which built massive pyramids that would serve as burial places and an entryway to the afterlife. The ancient Egyptians were so keen on mortality’s final stage that they developed a sophisticated philosophy and framework to prepare for death, and try to answer the (now) age old question of what happens after our physical bodies depart this mortal realm. The “Book of the Dead” is perhaps the second best known ancient Egyptian creation after the pyramids. It is actually not one book, but rather a series of illuminated texts describing funerary practices.

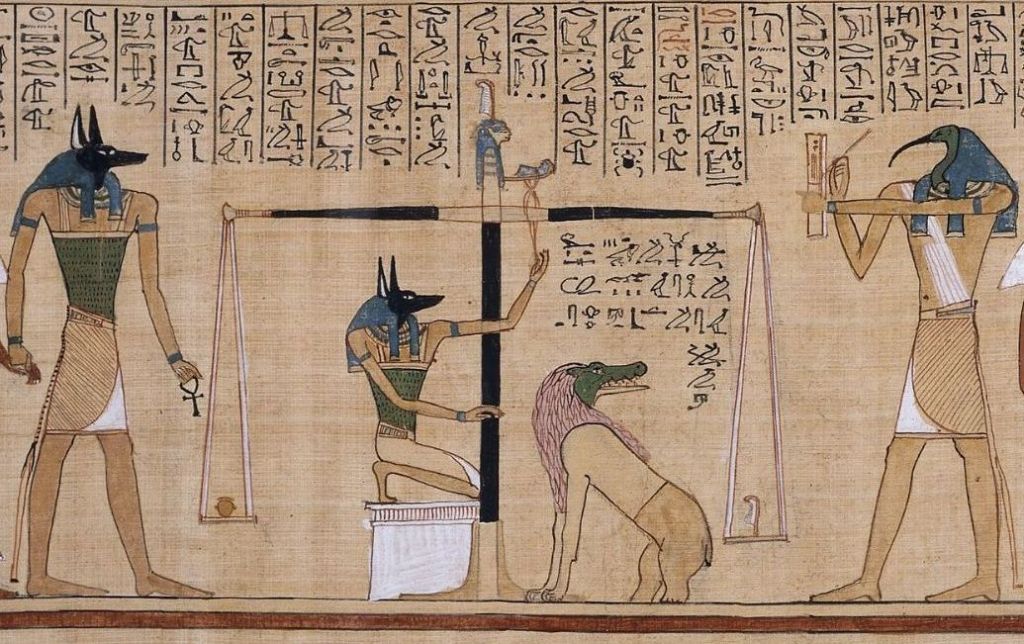

An example of familiar content within the “Book of the Dead” is the Papyrus of Hunefer (c. 1275 BCE), which describes and illustrates the impending eternal fate of Hunefer, a well known scribe during the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt. The process features a test conducted by ancient Egyptian deities. On the left hand side of the papyrus is Anubis, who leads Hunefer to a scale where Hunefer’s heart is weighed against Ma’at’s feather of truth. Thoth is present on the right as a scribe recording the consequential results. This scene shows how the Egyptians viewed death and the afterlife in regards to one’s individual life choices and the conventional moral code which governed Egyptian society. If a recently deceased person’s heart is equal to the weight of the feather, they are given permission to enter into the afterlife. If the heart is heavier, they are subsequently eaten by a vicious hybrid crocodile, lion and hippopotamus-like creature, known as Ammit. These narrative vignettes are some of the most common artistic renderings in the books of the dead. And in case you were wondering, Hunefer passed the test.

One of the major ancient Egyptian ideologies regarding how departed humans would function in the afterlife, was the theory of a second self called the “ka.” When someone’s corporeal self expired, the ka, which was inherent inside every human being, would experience eternal life. Perhaps they were onto something with this notion from not only a religious sense, but a scientific one as well. As we know from our basic school day studies in physics, matter never truly dies. In other words, despite our physical bodies expiring, the energy we create during our lives (this includes electrical impulses and signals and chemical reactions) does not actually die with us (see: Trosper, 2013).

Even with the scientifically supported knowledge and the metaphysical prospect of an afterlife, dying is largely an unwelcome part of life. It is one that is known to cause severe anxiety, depression and fear. This is why artists from ancient to modern times have used death as a theme in their work; often as a means to come to terms with life’s final frontier and suggest ways to cope with the aforementioned disparaging feelings around dying. In addition to being a vital coping mechanism, artwork that explores death can provide educational insights into the social, emotional and physical aspects of dying, thereby helping us prepare us for the inevitable.

A profound series by contemporary art photographer Stephen L. Starkman is a good example of how art enables us to find innovative ways of coexisting with the conundrum of continuing living our lives while knowingly dying. In 2021, Starkman was diagnosed with an aggressive type of cancer that doctors have concluded is terminal. At the time of this post’s publication, he has been given a relatively short timeline to live. Upon learning of his diagnosis, Starkman turned to the medium that has been vital to his life and career, and has been photographing the process of dying from cancer. Starkman’s imagery exploring mortality has been compiled in a narrative monograph titled The Proximity of Mortality: A Visual Artist’s Journey Through Cancer (2022).

© and courtesy of Stephen L. Starkman

In his series of photographs, Starkman presents both documentary and poetic compositions that make confronting death somewhat of a cathartic and comforting experience. Although these works of art depict a uniquely personal perspective, they are also representative of universally shared aspects of mortality and coming to terms with eventually dying. Starkman expressed this zeitgeist by collaborating with other cancer patients and survivors who contributed prose and poetry to accompany his photographs. Through the photographs, Starkman expresses a spectrum of feelings and insights that address pragmatic thoughts and responses to dying. Starkman’s art combines concrete representational imagery with abstract and metaphorical musings of the cycle of life and the potential for existence beyond death. An example of the more tangible tinged with metaphor is his stark framing of medical settings, such as a hospital waiting room and CT scan machine. Both photographs offer a glimpse into life with a terminal illness, as well as an expression of anxiety and grappling with the unknown. Looking into the empty corridor-like chamber of the CT scan machine makes me think of the phrase “a light at the end of the tunnel;” which in the case of Starkman’s art has two intersecting meanings. First, it symbolizes a long-awaited indication that a period of hardship or adversity is nearing an end. Second, it signifies undergoing a near death experience, which is often described by those encountering it as “going into the light.”

Other photographs in the series are less literal in their connection to physical illness, but just as poignant in their depiction of life’s ephemeral qualities. Starkman is incredibly poetic in the way he juxtaposes the institutional materialism of hospital wards with natural phenomena to represent both the physical and philosophical aspects of living with terminal illness.

© and courtesy of Stephen L. Starkman

Landscape-style photographs taken during drives or walks through the countryside or air travel reveal how everything in life is connected via nature. Finding solace in nature is a recurring theme in Starkman’s art. These images abstract and re-frame traditional landscape photography to make a conceptual connection between tangible life on Earth and unknown circumstances. Compositions that delineate between land or sea and the horizon are indicative of living on the precipice of life and death. The land might signify our physical existence, while the vast horizon refers to life after death. Viewing these photographs, I am drawn to the poem “Death is Only a Horizon” by Rossiter W. Raymond, especially the verse: Life is eternal; and love is immortal; and death is only a horizon; and a horizon is nothing save the limit of our sight.

© and courtesy of Stephen L. Starkman

Ethereal photographs of large gray cloud clusters juxtaposed with a background of blue sky elicits both an ominous and optimistic outlook on mortality. Metaphors such as the “calm before the storm,” can be interpreted from analyzing these compositions. Furthermore, you would not be remiss to connect the presence of clouds with the heavens.

© and courtesy of Stephen L. Starkman

Starkman’s skills as a photographer enable him to employ optical illusions that enhance the concept of mortality by blending both natural and supernatural forms. An example is his use of backscatter, a technique that results in circular artifacts appearing in a photograph that are not visible to the naked eye. This is due to the flash of the camera reflecting various unfocused particles in the air. The circular forms allude to supernatural orbs, which in paranormal investigations allegedly indicate the presence of spirits.

Starkman’s work highlights some of art’s major benefits, such as how it provides a well rounded record of humanity’s lived experiences and prompts inspired ways of dealing with death and the impermanence of human existence. This has significant pedagogical value, because it exemplifies how creating art helps us assess and confront our trials and tribulations. Making art about intimate experiences can be a way of punctuating the gravity of existential distress with hope and perseverance. Artists imbue messages into their work that they want to share with anyone who views it. This makes art a means for connecting with those who share similar perspectives to its creator, but also to inform viewers who have different views and backgrounds. Both the former and latter outcomes are how we hone our ability to exhibit empathy and partake in providing social and emotional support to others. In this manner, art is crucial to helping us understand and relate with major corporeal issues like illness, disability (see: “Art Integrated Medical Awareness and Education”) and death (see: “Artfully Grieving”).

Most artwork will outlive its maker. Starkman’s art will serve as a living legacy for both his artistic accomplishments and as a resource for others who are going through seemingly impossible life experiences. His artistic series illustrates the saying “hope springs eternal.” This is aptly reflected in his own words, “peeking around the corner is fear — and a clock that is ticking. And yet, I still want to have hope” (quoted in Moya Ford, 2022). It is human nature to explore, discover and express reasons for optimism. Not only has this process been beneficial to Starkman’s outlook on his mortality, but it has the potential to impact and inform the actions and attitudes of others who are facing similar outcomes.

References, Notes, Suggested Reading:

Moya Ford, Lauren. Hyperallergic, 1 February 2022. https://hyperallergic.com/796797/photographer-stephen-starkman-captures-his-journey-with-terminal-cancer/

Raypole, Crystal. “How Many Thoughts Do You Have Each Day? And Other Things to Think About,” Healthline, https://www.healthline.com/health/how-many-thoughts-per-day

Starkman, Stephen L. 2022. The Proximity of Mortality: A Visual Artist’s Journey through Cancer.

Trosper, Jamie. “The Physics of Death (and What Happens to Your Energy When You Die),”18 December 2013. Futurism, https://futurism.com/the-physics-of-death

Tseng, J., Poppenk, J. Brain meta-state transitions demarcate thoughts across task contexts exposing the mental noise of trait neuroticism. Nat Commun 11, 3480 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17255-9

Discover more from Artfully Learning

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.