Curricula is always in flux, yet sometimes we get too comfortable or complacent with what we know, or perceive to be worth knowing. The common core, core knowledge and other curricula seek to find a ‘universal’ set of standards, goals and information that would enable a collective society to have a similar understanding. These types of systems form a canonical framework for education, much like the way art history has been presented and understood through the canon; a set of self-evident principles and rules that govern a conventional model for teaching what is believed to be worth seeing and knowing. The issue is that those who design the aforementioned curricula or who write art history as a linear and prescribed narrative, are often at odds with presenting an equal and equitable reality of the human experience.

This post will critique the canonical framework for the study of art history, and how contemporary curricula, such as the new AP Art History course and pluralistic cross-cultural exhibitions in museums have shifted the canon away from traditional Eurocentric and binary modes of analyzing, researching and discussing art.

An essential question, that is worth contemplating is how the artworks we are most familiar with and deem most valuable get that way? How did the halls and galleries of museums get established and the narrative of art history become the basis for idealizations of beauty and symbols of wealth, power and knowledge?

An enduring understanding, is that art history is a discipline based on both an account of the stylistic and conceptual stages of art, as well as the bias or personal taste of the people who record and present it. There are factors that contribute to this scenario including: patronage, colonialism and academic or institutional status. For example, art historians have had a role in propagating the masterpieces of classical civilizations like Greece and Rome, as works of art symbolize beauty, balance and an ideal democratic ideology, while describing work outside of this classical tradition as ‘primitive’ or ‘tribal’ (see: Breukal, 2011). They have elevated the works of certain artists, styles and cultures who adhere to their standards of what makes for good form, content and context. They also dictate what is art and what is not, such as when, in the 18th century, Johann Joachim Winkelmann defined art by its aesthetic nature –to categorize the form, content, and context of Ancient Greco-Roman art– or when centuries later, Arthur C. Danto (using Hegel’s thesis “end of art” as an influence) argued that art isn’t as much about aesthetics as it is about its concept and intent. The media that was used, the style of the art, or who the artist is that made the work is not as important as the physically embodied meaning. In this day and age, artworks don’t have to fit into prior art historical categories to be considered a part of the artistic narrative. In fact, Danto argues that art hasn’t had a linear progression since the end of the Modernist era (c.1960s-70s).

Because Danto’s argument shatters the preexisting model of how art is defined, it re-posits the age old question of ‘what is art?’ and who gets to define art. To answer that philosophical question, Danto formed the foundation for an institutional theory of art in his seminal text ‘The Artworld.’ In Danto’s definition of the ‘artworld,’ something is art if those who have erudite and/or content specific knowledge about art deem it to be art. The ‘artworld’ is more than a philosophical space, it shapes the very fabric of our culture and how we value objects and essentially each other.

It is evident that the art historian, critic and patron have nearly as much influence on our perception of art as the artist or artwork itself. Flip through any survey textbook and take note of how many of the same images of artworks you see. How many of these works are by artists who are white? How many are male? How many come from European or colonial American backgrounds? The same goes for museum collections. Both these textbooks and museum collections have been shaped by generations of canonical reinforcement. While art history and the institutional art field is concerned with presenting narratives that give context to people, places and events throughout civilization; specific people, places and events become marginalized via their methodology.

Art historian Robert S. Nelson (1997) warns, “As a discipline, art history acquired and has been accorded the ability to reject people and objects, and to teach and thus transmit values to others…If these structures are seldom noticed, much less studied, they are always present. They are revived and replicated whenever a student attends an introductory class, reads a survey book, or follows a prescribed curriculum….” Fortunately, some people within the artworld are noticing this, and finding engaging ways to address this problem.

While taking an art history survey course in college, Titus Kaphar realized that the course content had been whitewashed to reflect Eurocentric ideals and images of affluent white male figures. Noticing that art made by artists of African descent was only a short segment within a larger textbook, and the reaction of indifference from his professor when he asked why the class had skipped over those topics, prompted Kaphar to look closely at the ways that black figures have been treated within historical works of art. These insights have led to his seminal artworks re-examining of Western civilization, which revivify and highlight the African American subjects who have been marginalized throughout art history.

Kaphar’s painting, Shifting the Gaze, is a repainting of Frans Hals’ Family Group in a Landscape (c.1648), a 17th century portrait of a wealthy Dutch family standing in front of a lush forest near the shore. While the family is portrayed distinctively so that we know they are of a particularly noble status, Hals mysteriously included a black boy in dark clothing, sandwiched between the mother and daughter. His positioning seemingly several inches behind the family, gives the perspective of his being nearly invisible. If not for his white collar he’d hardly be seen at all. His brown skin and tunic blend into the dark green and brown tones of the trees in the background. He actually becomes more of a background formal element than a contextual figure within the painting. In the object description by the head curator of Old Master painting from the museum where the work is held, the dog next to the daughter –ironically rendered nearly as invisible as the boy– is mentioned and analyzed, while there is no acknowledgment of the boy’s presence whatsoever.

The perplexing inclusion of this figure and the absence of any proper identification or biographical information, is consistent with the way Kaphar noticed black individuals being portrayed within traditional European and American paintings. In order to shift our gaze to this unequal and inequitable issue, Kaphar took a large brush, dipped it in white paint and essentially covered up the Dutch family so that our attention is solely drawn to the black boy, thereby amending the form, function and context of the original Dutch portrait. Eventually the translucent quality of the paint he used to mask the Europeans will lightly fade over time (but still masked), creating a portrait where everyone is represented more equitably.

The new AP Art History curriculum and art history courses on the college level can do a great service to amending past art historical bias and omission. Through focusing more on art made throughout the world and presenting it in a manner that supports active learning, the new AP Art History course is designed to give students agency to think critically and outside of the box. By narrowing the content down to 250 required works, teachers can supplement these works with other examples that broaden students’ skills to closely observe works of art, make formal, contextual and sociocultural connections between works of art –with a heightened awareness for connecting works spanning time and place– and critically question and examine problematic narratives (or lack of specific narratives) previously attributed to works of art, styles and geographical locations. These are all important habits of mind that build students’ skills to develop empathy for the world around them, find patterns within the human condition and poignantly address ambiguity about questionable historical analysis and bias.

By using works both within and outside the required 250, teachers can prompt students to research specific works of art that have complex sociocultural context and critique degrees of interpretations from reputable sources. The goal is not to feed them didactic knowledge about each work, but enable them to formulate their own original thesis on why art is made, how art changes meaning over time (essential questions within the curriculum) and how historians might address bias within traditional meanings and interpretations.

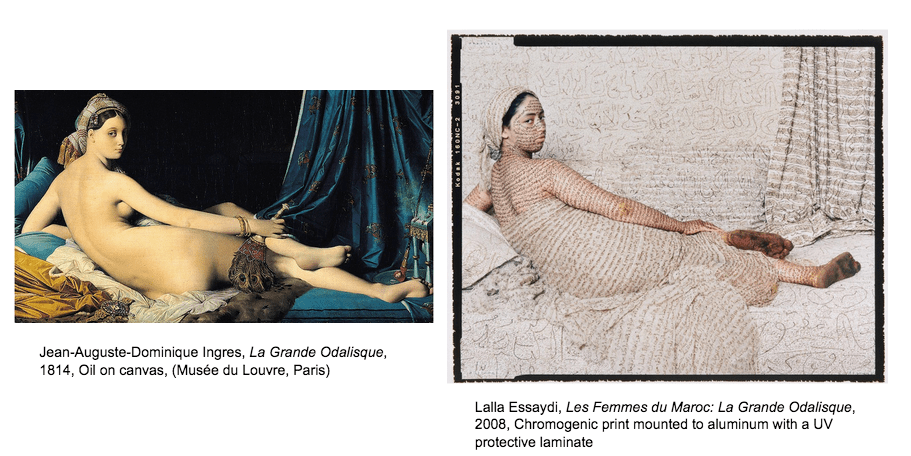

For example, each of the painting sets below feature a work from the 250 paired with a contemporary example of a work that offers an amendment to tradition. Students can take close look at each of these works, compare and contrast the content and context and make inferences about what each artist on the right of each image set is expressing in rebuttal to the artists on the left.

Enduring Understanding: The male gaze, portrayal of the ‘other’, ideals of beauty, power, and seduction are ripe motifs throughout the Western art historical canon.

Essential Question(s): How has the form, function, content and context changed from the painting on the left to the painting on the right? How has the traditional portrayal of these 19th century paintings been amended by 21st century contemporary artists? What issues are being addressed in the contemporary works of art?

Dr. Robert Glass writes: “Art historians ponder and debate how to reconcile the discipline’s European intellectual origins and its problematic colonialist legacy with contemporary multiculturalism and how to write art history in a global era.”

The study of art history in primary, secondary and higher education, should give students agency to make significant and critical inferences by making art meaningful to their lives. This can be done through active learning and also by making the content more relatable and equitable to a wider and more diverse student body. There is still a major equity and equality problem both within academic art and institutional art environments. There is no easy solution that will rectify present and past injustice. However, if the study of art becomes more pluralistic and relevant to students’ lived experiences, perhaps schools will see an increase in the diversity among students who are studying art history. Perhaps these students will go on to shatter the canon once and for all…

References, Notes, Suggested Reading:

Breukel, Claire. “WTF…Is Primitive Art vs Tribal Art.” Hyperallergic, 14 Sept. 2011. https://hyperallergic.com/35460/primitive-art-vs-tribal-art/

Danto, Arthur C. “The Artworld” (1964) Journal of Philosophy LXI, 571-584.

Glass, Dr. Robert. “What is art history and where is it going?” Khan Academy. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/approaches-to-art-history/an-introduction-to-art-history/a/what-is-art-history

Discover more from Artfully Learning

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Great post!

It made me think of my own art history education at primary and high school level, how it was mostly focusing on the ‘geniuses’ and ‘old masters’. I also don’t think we need to publish so many of those ‘100 paintings-you-have-to-see-before-you-die’ books these days, since the majority of artists included are usually repeated over and over in similar publications.

Maybe if during our school years we were exposed to more varied art, from around the world, we would become more open in our adult lives. Old-fashioned education leads to comments like ‘not conventionally beautiful’ or ‘beautiful in a traditional sense’, usually applied to so-called non-western art. We need to see the bigger picture.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the reply! I think that you’re spot on about those ‘100 paintings’ books and other ‘highlights from the collection’ guides, which simply reinforce the canon and –in my opinion– don’t allow for critical thinking or inspire one’s sense of exploration. I see so many people crowded around the works that are reprinted in guides, posters, brochures, museum signage etc, that they are at risk of missing the incredible works from other cultures and other artists that are not widely disseminated. There’s actually a segment on the show “Adam Ruins Everything” where he shows how the more familiar a person is with an image, the more they like it…They often conflate familiarity with liking something without including any additional critical thinking. Not that a popular TV show is the best source, but it was interesting nonetheless, and I’ve witnessed this myself in museums and galleries… Thanks again for reading and for your comment!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes it seems to be true quite often – the more you see something the more you will like it. Yet there can be too much of a good thing. I actually ‘stopped liking’ some of my old favourites because of how commercialisation killed their appeal for me.

Take care,

Weronika

LikeLiked by 1 person

Because I have studio art degrees and because they are not in either painting or sculpture, I have spent most of my adult life thinking about how we define art, about how art reflects and challenges mainstream culture and how these interactions both motivate and drive me as a creative person.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is an essential question that I find necessary to ask before even delving into making, discussing and writing about art. I often find that people I engage with who tell me they ‘don’t like art,’ haven’t actually thought of how they define art, and how their prior experiences may have shaped their opinion about art. Once we get the ball rolling in those directions (and with a little introduction to the foundations of artistic discourse), I find that everyone has something important to say about art. Like most things, the definitions are fluid and everyone has their own informed perspectives, which is the crux of the enjoyment I get from sharing artful experiences with others!

LikeLiked by 1 person