The Reverend Jesse Jackson passed away today. Along with Shirley Chisholm (the first Black woman to be elected to the United States Congress), Jackson had a major role reshaping and restructuring the entire course of the Democratic party. Jackson envisioned the United States as a metaphorical quilt, with “Many patches, many pieces, many colors, many sizes, all woven and held together by a common thread.” That sentiment signifies the basis of Jackson’s life’s work to seek and uphold social justice through a plurality of ethnic, racial, religious and economic backgrounds. He frequently referred to this diverse camaraderie as a rainbow.

In 1971, Jackson’s rainbow analogy was front and center in the establishment of his Rainbow/PUSH (People United to Save Humanity) Coalition, a name that he co-opted from Fred Hampton’s Rainbow Coalition. Hampton was the deputy chairman of the national Black Panther Parry, and the architect behind the earlier Rainbow Coalition, which was implemented in 1969, as an anti-racist and socialist political organization for various marginalized communities in Chicago, Illinois. One of the many significant and beneficial contributions from the Rainbow Coalition was improving the accessibility and quality of public education.

While the Rainbow/PUSH Coalition, which became the National Rainbow Coalition was more moderate than Hampton’s revolutionary Rainbow Coalition, it also focused on empowerment of youth and community via the investment in progressive public education. Additionally, Jackson’s organization became a significant political force, which was responsible for expanding the Democratic party’s base through the enthusiasm of Black and brown voters. Data that shows that when the Black and brown voting bloc shows up at the polls, they are a demographic that has significantly helped specific candidates win elections. Jesse Jackson’s organizing and advocacy for Black voices in politics was largely responsible for this sociopolitical shift. The powerful influence of the Black and brown voting bloc is why Republicans have ramped up fear-mongering and disinformation campaigns aimed at suppressing the vote in predominantly Black and brown communities.

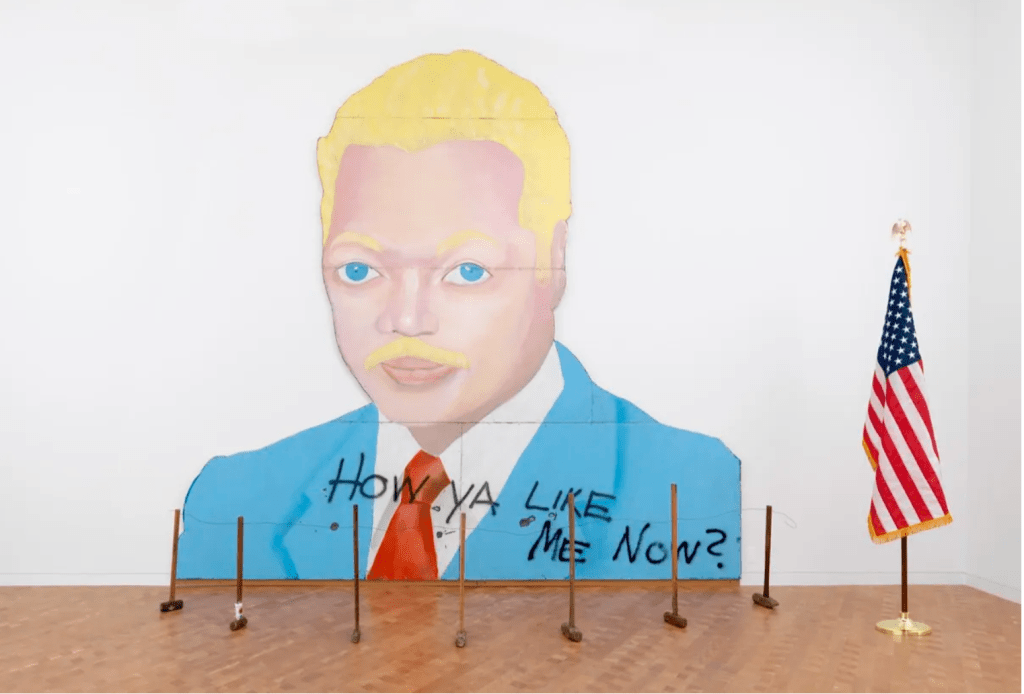

In memoriam of Jackson’s life and legacy, and in light of the Trump administration’s recent push to advance racially biased voter disenfranchisement, it is apt to revisit a 1988 installation by artist David Hammons’ titled How Ya Like Me Now? Hammons’ mural sized painting, measuring fourteen by fourteen feet depicts Jesse Jackson as a white man with blonde hair and blue eyes. Underneath the portrait Hammons spray painted the question, “How ya like me now?” In front of the painting are sledgehammers, arranged upside down to form a protective barrier for the painting, which also resembles a velvet rope stanchion used for crowd control at events. To the right of the painting stands an American flag on a pole with a golden eagle on top. The symbolism of the sledgehammers reflects failed efforts by a group of people to smash the painting with sledgehammers while it was being installed outdoors as part of an exhibition titled The Blues Esthetic: Black Culture and Modernism, in Washington, D.C. The painting’s placement at 7th and G Streets, situated it directly across from the National Portrait Gallery.

How Ya Like Me Now? poses fundamental questions and issues around racial identity in the political and cultural sphere. Most evidently, it prompts viewers to consider whether Jackson would have been perceived and treated differently when he ran for President in 1984 and 1988, if he was a white man. Hammons’ statement, “I think if Jackson had been white, he would have been elected long ago,” supports the painting’s main overtone. One major critique coming from Jackson’s political advocates was that journalists had relayed a racist and narrow-minded characterization of Jackson in the media, suggesting that he was a stereotypical loudmouthed Black preacher.

The aforementioned iconoclastic attempt on the painting speaks to the theme of racial bias, albeit in an ironic fashion. The ten people who sought its destruction were Black men, who were unfamiliar with Hammons’ work, and assumed the painting was a racist affront to Jackson’s character, akin to the biased portrait the media painted of him. In that regard, the initial intent behind Hammons’ work was largely successful.

Jackson’s vibrant and inspirational persona influencing works of art is no coincidence. He supported the main empathetic tenets behind the creation of art, which is the application of both imagination and a grappling with real life issues and experiences. He elaborated on these aspects in a rousing and memorable political speech at the 1988 Democratic National Convention: “You must never stop dreaming. Face reality, yes, but don’t stop with the way things are. Dream of things as they ought to be. Dream. Face pain, but love, hope, faith and dreams will help you rise above the pain. Use hope and imagination as weapons of survival and progress, but you keep on dreaming, young America. Dream of peace. Peace is rational and reasonable. War is irrational in this age, and unwinnable.”

Rest in power, Jesse Jackson.

Discover more from Artfully Learning

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.