Another school shooting happened this week in the United States of America, which already amounts to a handful of horrific and preventable tragedies just mere weeks into the start of the new school year. This should be a time when students and faculty enjoy icebreakers and the enthusiasm to learn in a collaborative setting. The reality is that too many educators and learners go to school fearing something that is uniquely and deplorably a cultural phenomenon in the United States.

I strongly believe in the potency of art and arts education as a means for real transformative policy change. However, while art education notably raises our collective consciousness to societal issues, and builds our social and emotional vocabulary so that we become more empathetic and responsive; it is clear that in order to address the root of the problem in every single case of gun violence, legislation must pass to directly deal with the problem, which is access to guns themselves.

Our elected officials can largely put an end to this crisis by enacting serious gun control legislation. Prior to sitting down to write this piece, I made another round of calls to my local and national representatives asking them to do so. Aside from legislation, another issue regarding the epidemic of gun violence is the public’s awareness and sensitivity towards it. I hate to think and surmise that there is a population of people who are actually desensitized to gun violence due to its commonplace status; but comments from some 2A advocates leave little to the imagination regarding how some people believe that owning guns is more important than the lives they take.

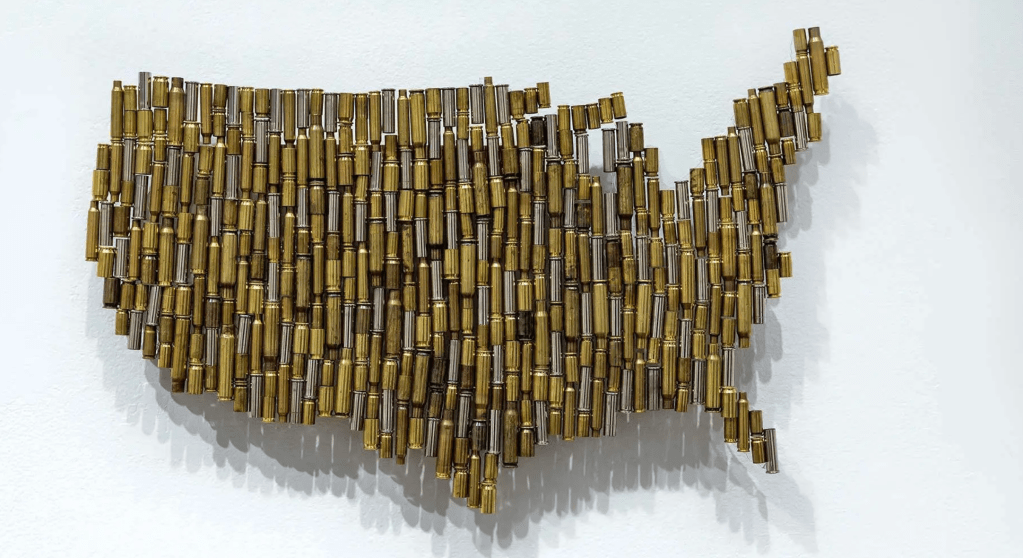

Courtesy of the Félix González-Torres Foundation.

What art does quite profoundly, is put horrific statistics, like shooting deaths, into a framework that prompts contemplation and reflection. In 1990, Félix González-Torres created and displayed Untitled (Death by Gun), an installation of large printed paper stacked around nine inches tall. On these sheets are names and photographs of 460 individuals killed by gun violence in one week in the United States. Like many of his sculptures, this one is interactive. He intended to keep the work as an open edition, which means that numerous copies can be made. And viewers are free to take an entire sheet for themselves.

González-Torres’ makes a truly compelling statement, but for me the artwork contemporary students make about gun violence is even more impactful, because they are the generations most effected by its prevalence. I facilitated projects in high school art studios where students have been asked to come up with an aesthetic campaign for an issue of their choice. It came as no surprise to me that violence and gun control were among the top five issues presented via works of art.

Just do a simple online search for “student art about gun violence,” and there will be ample results. It is sobering and unsettling that students have to respond to these issues at all. But unfortunately gun violence is an enduring legacy of students in the U.S.A, and until it ends artwork will be a major avenue through which they express to our policy makers and our collective consciousness that enough is enough.

In a relatable context to González-Torres’ installation, art student Mary Mena’s Neverending (2024), fashions together 321 bullet casings in the shape of the continental United States as a depiction of the 321 people shot each day in the United States.

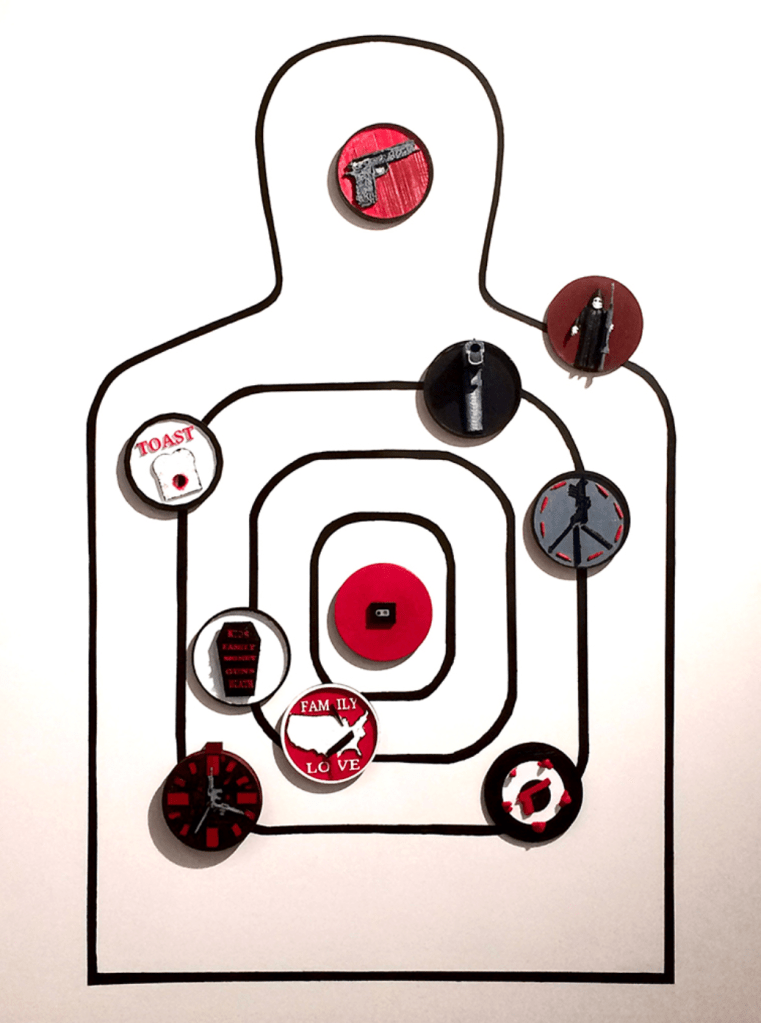

Another stirring work of art is a multimedia piece titled, Silence the Violence (2018), created by students from Southern Connecticut State University takes the shape of a target practice silhouette on paper. Affixed to the target are several sculptural relief vignettes using a 3D printer, which reference the contentious and highly partisan debate over gun control regulation; and the manufacturing of guns using a 3D printer, which makes them much easier to access and harder to trace.

Courtesy of Connecticut State University.

In 2020, I wrote: “It is indeed possible for art to stop the initiation or continuation of violence, as well as the oppression and marginalization of diverse individuals and groups. By incorporating the lessons and skills that the arts teach us, such as thinking outside the box, collaboration and placemaking, making cross-cultural connections and developing empathetic understandings; we can become creatively adept at handling the nasty curve balls life throws at us and expressively advocate for social, cultural, economic and environmental justice for all.”

I am not as assertive about that sentiment nowadays. Especially because the foundation of public education is being chipped away and politicized in ways that enforce censorship and the dismantling of humanities like the arts and social studies. Subjects that had the ability to inspire critical dialogue and empathetic responses to historical and contemporary trauma are so neutered and whitewashed, making the work of educators harder and messier than ever before. Not to mention the fact that they are also being asked to be responsible for stopping mass shootings. It is an unreasonable, unsustainable and ignorant stance that is indicative of a society governed and influenced by callous people. The typical “thoughts and prayers” are vapid and blasphemous offerings, especially coming from the mouths of some of the most egregious advocates for upholding the status quo of gun violence in America.

Enough is enough, but when will it actually be enough for it to end?

Discover more from Artfully Learning

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The ways the arts in education are being eroded in your country is not that dissimilar to what is happening here in New Zealand. Educators have it tough in trying to portray the wider implications for society, if the arts and social sciences continue to be undervalued in our schools. Where will diverse and creative ideas spring from, if not from the classroom? Regards, Vivienne

LikeLiked by 1 person

Education is a battlefield when it should be a sanctuary. And that’s one of the main reasons why the United States and other “western” countries are experiencing the wide-scale erosion of our democratic foundations.

We cannot claim to be an enlightened, innovative and just society, when violence, censorship and bigotry are at the forefront of our collective culture.

LikeLike