This piece is a reworking of previously published posts on my Artfully Exercising platform.

I have vivid memories of turning on my ten-inch black and white television set circa early 1990s, and seeing the Bally Total Fitness commercials. One of the most astounding examples aired in 1993, featuring cinematic black and white vignettes of men and women working out in sheer ecstasy.

Although incredibly idealized with regards to body image, this commercial did portray some truisms about the connection between body, mind and spirit. One of the phrases, “Body = temple, act of worship and baptism by sweat” is a particularly provocative declaration.

The Bally’s commercial, which was inspired by conceptual contemporary art (I’ll speak more on that later), came out during the height of the culture wars where conservative religious and political institutions united in an effort to impose their ideologies across the entire United States. Art that broached topics of religion and identity in a liberal and critical manner were targeted for censorship by these aforementioned groups. Even today, some might take offense to the use of religious vocabulary in order to sell gym memberships. However, the statement that our bodies are sacred has value and is well worth preaching. Our bodies should be absolutely venerated, which will mean different things to different people; but the message derived from a good mind/body relationship is clear: treat ourselves with love and kindness.

Bally Total Fitness was the most renowned gym franchise in the United States during the late 1980s and throughout the 90s, and it owed much of its success to Jack LaLanne who opened the first public gym in 1936. He actually sold his very successful brand of gyms and health clubs to Bally in the late 1980s, hence why the commercials had his name written underneath the Bally logo. If you have used a Smith Machine, resistance bands or eaten a protein bar, you have LaLanne to thank. He invented them all!

LaLanne was both the premier gym advocate and one of the first major fitness influencers in the United States. The Jack LaLanne show is the fitness equivalent to Julia Child’s The French Chef and Bob Ross’ The Joy of Painting. Each of these programs made their respected craft (fitness, cooking and painting) accessible to the masses. LaLanne understood that everyone’s body and needs are distinct to their own lived experiences. Therefore, he acknowledged modifying and pacing certain exercises so that they can be performed by everyone watching his program.

The zeitgeist of making wellness and weightlifting accessible to the masses existed within the spectrum of body politics being discussed and expressed during the 1990s. On one end, there was “heroin chic,” a trend that glorified incredibly thin bodies; on the other there was the gym culture of lean, muscular bodies. The heroin chic look was popularized by supermodels like Kate Moss in fashion magazines and catwalks. Alternatively, the toned physical aesthetic was promoted by LaLanne and a number of fitness models. Both looks, while representative of stark opposing beauty and lifestyle standards, were presented as “sexy.” Big box commercial gyms like Bally’s capitalized on the popularity of models like Suzanne Somers and Cindy Crawford who each were associated with a series of wellness campaigns and products.

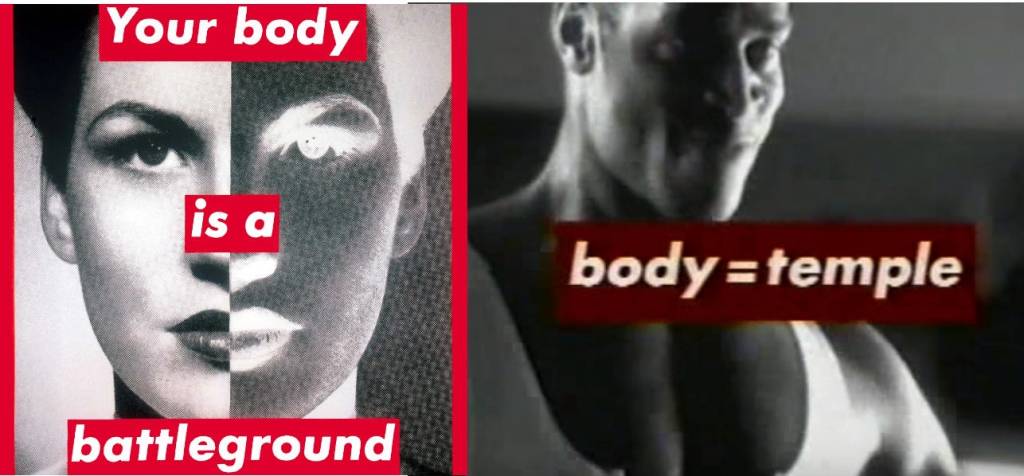

My ten year old sensibility did not form a riveting critique of the 1993 Bally’s ad, but revisiting the commercial today (with a Master’s degree in art history), I immediately saw an appropriation of Barbara Kruger’s iconic artwork; specifically her works Untitled (I shop therefore I am) and Untitled (your body is a battleground). Kruger’s style and process consists of taking black-and-white photographs and overlaying them with declarative and critical captions, which are boldly presented using white-on-red sans serif typefaces.

Below is a side-by-side comparison of Kruger’s Untitled (your body is a battleground) from 1989 and a still from the aforementioned 1993 Bally Total Fitness commercial:

As an artist Kruger also assumes the role of a social critic by addressing the grip of media, consumerism and politics on shaping our behaviors and ideologies, such as body image and gender.

Both the disciplines of visual art and fitness have a major role in shaping cultural outlooks on body identity, so the cross-examination and representation of fitness through an artistic lens can be profoundly apt.

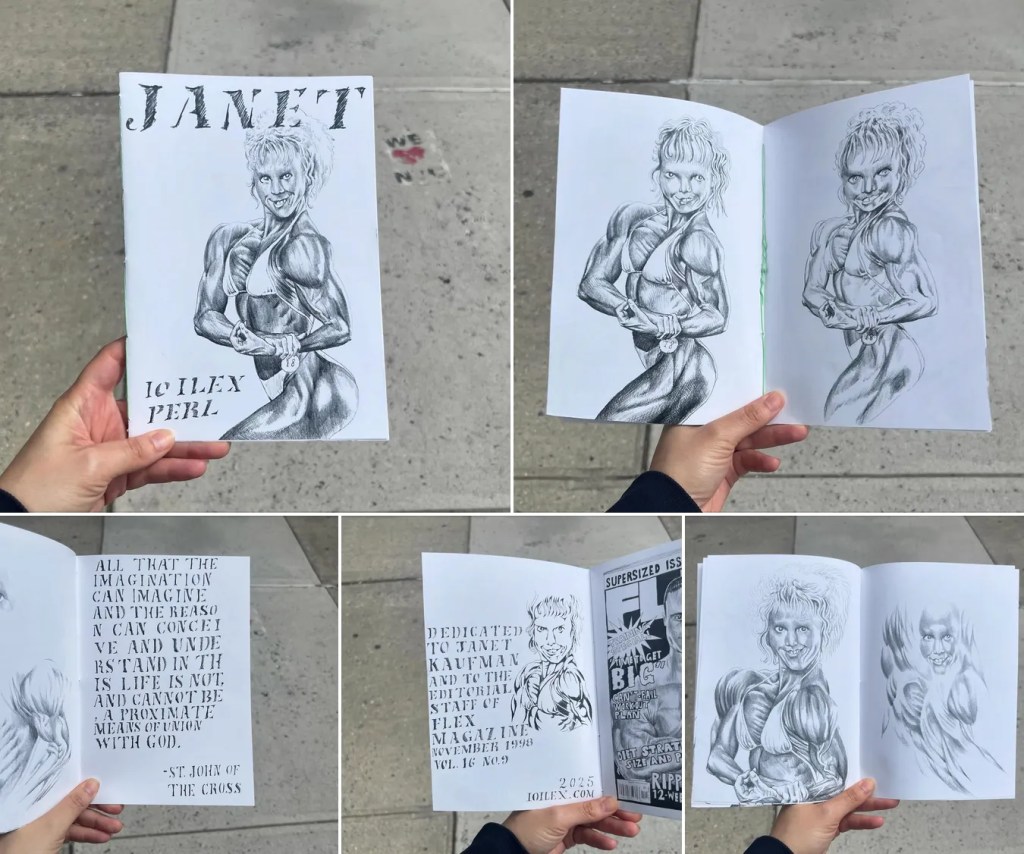

In a zine by artist and anthropologist Io Ilex Perl, titled Janet, intricately rendered drawings referencing a photograph of bodybuilder Janet Kaufman (which were initially published in the reader mail section of the November 1998 issue of former bodybuilding magazine, FLEX) address the push and pull between the profane and sacred within the culture of bodybuilding.

Like a bodybuilder repetitively lifting weights, Perl flexed her draftsperson’s muscles in replicating Kaufman’s likeness so many times throughout the zine. Her drawing and video art practice involves a devotion to portraying extreme physical disciplines like bodybuilding, body suspension and boxing through the lens of an artist.

Alongside one of the drawings of Kaufman is a quote from St. John of the Cross, which reads: “All that the imagination can imagine and the reason conceive and understand in this life is not, and cannot be, a proximate means of union with God.”

I am Jewish, so I have very limited familiarity with St. John of the Cross, or most Catholic scriptures for that matter; but I find his quote compelling, especially in light of how Perl juxtaposes it with her imagery of bodybuilders.

I spent a significant chunk of time pondering over this quote. From my novice interpretation, St. John of the Cross is prompting Christians to embody an active purification of the senses and spirit, in order to obtain a truly authentic union with God. The best summation I came across was from writer Tom Mulcahy, who notes that: “Understanding is to be replaced by faith, Memory is to be emptied and forgotten and replaced by hope, (and) The will is to be emptied of all desires save that of loving God with all our heart, mind and strength.”

This essentially means cleaning one’s physical and mental facilities of all distractions, addictions and vices, which hinder an individual’s ability to focus on supernatural knowledge and virtues. In this regard, I would initially conclude that bodybuilding would particularly be an endeavor that is antithetical to the concept of spiritual purity; in part because bodybuilding is reliant upon corporeal desire, as well as the use of anabolic steroids. However, some might suggest that building physical strength and the virtues of active purification are interlinked. Bodybuilding is far more than just seeking a specific type of corporeal aesthetic, it requires a significant amount of dedication, focus and devotion; and is a ritualistic practice that necessitates a concerted abstinence of specific bodily and emotional urges.

Interviews with Kaufman (and any other bodybuilder for that matter) elucidate the strict mind and body commitment that’s required to develop and sustain her status in the sport. For example, she’s up at dawn, trains multiple times throughout the day, sticks to a “clean diet” that is high in protein and goes to bed early. While St. John of the Cross would more than likely disagree with the comparison, this unwavering schedule and process is akin to the tenets of active purification.

Throughout Christian texts (and quotes by popes, preachers and saints) the body is often considered a temporary vessel, and in order to make room for the holy spirit, we should work diligently and passionately to refine specific traits and attitudes that embody virtuous aspects which bring us closer to God. Prior to the age of enlightenment, several religious philosophies were concentrated in the idea of holy suffering, or asceticism, which is the denial of worldly pleasures through rigid self-discipline.

Bodybuilding could be interpreted as ascetic (i.e training to failure and/or discomfort and the removal of certain bodily pleasures and excesses like sleeping in and culinary indulgence, save for the occasional “cheat day”); but working out at large, especially strength training, is not self-punishing. The release of endorphins and the reward from a hard and taxing workout, often leads to euphoria. The challenges and rewards of exercising might also have an impact on a person’s ability to express empathy, which is the ability to understand and share another person’s feelings. A paper published in the peer-reviewed scientific journal Frontiers, posits that: “It is widely known that exercise has a beneficial effect on human behavior, and recent studies have shown that empathy is no exception. It may be suggested that if exercise activates the mirror neuron system while exercising, individuals may experience increased levels of empathy while exercising.”

From the age of enlightenment (formally discussed in Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s 1762 publication, Emile)onward, the process of building strength through exercise has been noted as a means to achieve righteousness and shape moral character. A principle called “Muscular Christianity” coincided with the Bronze Era of Bodybuilding during the late nineteenth-century. The term was proliferated by the writings of English author Thomas Hughes, who states in his 1861 novel, Tom Brown at Oxford, that: “the least of the muscular Christians has hold of the old chivalrous and Christian belief that a man’s body is given to him to be trained and brought into subjection, and then used for the protection of the weak [and] the advancement of all righteous causes.”

When Cardinal Robert Prevost ascended to become Pope Leo XIV, an article was published mentioning that his personal trainer Valerio Masella didn’t realize he was training such a high profile Catholic client. The article states that: “A typical workout for someone of Prevost’s age, 69, was a mere warm-up for the little-known American cardinal…Although it is hard to define an age group for personalized programs, Prevost’s plan was more befitting of men aged 50-55. Masella would train him two or three times a week in sessions lasting up to an hour.”

There is far more to unpack and understand from the world of bodybuilding and fitness training in general than the outward appearances of its notable practitioners. If we consider that our muscular bodies are vessels for radical and righteous love, we can harness that power to lift ourselves and others upward and onward. We can apply the passion, dedication and empathetic aspects of exercise as a way to get in touch with our humanity, be a pillar of support in our community and find spiritual or otherworldly meaning and experience in life itself. That to me, is a quintessential example of pure strength and devotion.

Discover more from Artfully Learning

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.