Like previous Pop Artists Andy Warhol and Jasper Johns, Frank Buffalo Hyde utilizes images and objects from popular culture as raw materials for his art. Buffalo Hyde, who was raised on the Onondaga Reservation in New York state, ironically emphasizes Americana through acerbic reinterpretations of material culture and Indigenous tradition. His paintings and sculptures are both celebratory and critical of the prevailing cultural landscape and zeitgeist within the United States.

As an Indigenous artist, Buffalo Hyde is acutely in tune to communicating how Americana, a term encompassing objects and phenomena associated with the culture and history of America, especially the United States, has eschewed, erased and exploited certain narratives from marginalized communities like Native Americans. An example is sports, where team mascots, logos and names have appropriated Native culture and exaggerated features and traditions that are insensitive to Indigenous communities (i.e. the former Cleveland Indians team name and logo and the “Tomahawk Chop”). Another instance is in movies and television, where Native American portrayals have upheld inaccurate stereotypes ranging from being barbaric assailants to peaceful but naive inhabitants of nature. The embodiment of Indigenous characters by non-Native actors is further indicative of systemic bias and a lack of empathy for Native American culture.

Buffalo Hyde’s paintings, sculpture and installation prompt us to consider what white supremacy and colonialism has done to displace the Indigenous people, their traditions and land. In No More Rushmore (2022), he paints the rocky landscape of the Black Hills region of South Dakota sans the monumental granite faces of U.S. presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln. Mount Rushmore is an iconic memorial that celebrates the achievements of colonial America, while disregarding that it has been carved into sacred Native American land. In fact, the land had been illegally taken from the Sioux Nation in the late 1800s. While the Sioux would have clearly preferred having their landscape left unaltered, the initial proposal for the carving, proposed by a historian named Doane Robinson, had distinct Native American representation including Lewis and Clark’s expedition guide Sacagawea, Oglala Lakota chief Red Cloud, Buffalo Bill Cody and Oglala Lakota chief Crazy Horse. However, the project’s main architect, a sculptor named Gutzon Borglum overrode that suggestion and settled on the four popular presidents. Borglum was a known sympathizer of the Ku Klux Klan and designed a Confederate monument in Stone Mountain, Georgia dedicated to Civil War generals Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee, and former President of the Confederate States of America Jefferson Davis (see: Newsome, 2021). No More Rushmore is a revised memorial in and of itself, reminding us that memorializing particular individuals or events can simultaneously disenfranchise and dishonor other people’s culture.

Courtesy of the artist.

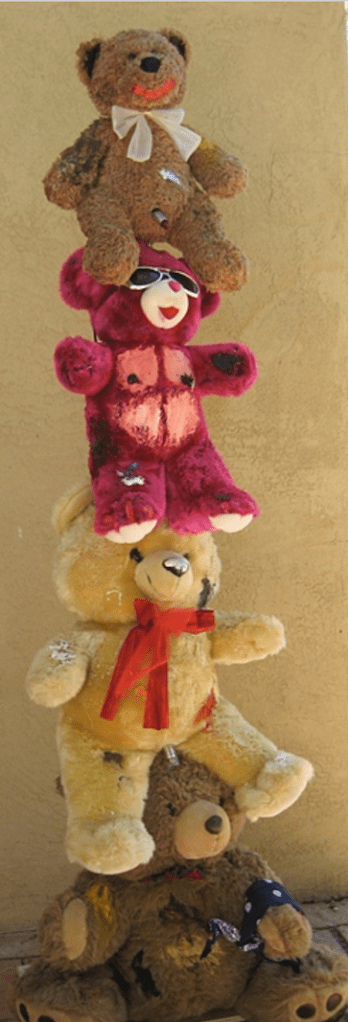

Another body of work from Buffalo Hyde’s oeuvre is his “Teddy Bear Totem” series. Creating sculptures using mass produced toys to resemble totem pole structures addresses the commodification of Indigenous American culture. Across the United States, totem poles have become divorced from their initial purpose. They are sold in gift shops and used as roadside attractions or advertisements to sell goods or services. All too commonly, appropriating totem poles is an endeavor carried out by non-Native individuals and businesses. This is even more egregious considering the colonial United States and Canada has had a fraught history with allowing Indigenous peoples to celebrate their cultural heritage and make a living from their crafts. An example is the Canadian government’s ban (from 1184 to 1951) on potlatches, which is a ceremony whereby Indigenous communities gather to destroy items of wealth or commodity in order to refocus and reaffirm their commitment to family, tribal nation and the spiritual and natural realms. Therefore, marketing totem poles as trinkets and tourist traps is an action of white supremacy that displaces both the spiritual object and the originators of these symbolic structures.

From a pedagogical standpoint, Buffalo Hyde’s work is exemplary in highlighting the use of material culture as a means for teaching and learning, and the importance of decolonizing education curricula in the United States (see: Reza, McEwan and Calvo-Hobbs, 2022). Teaching tools like textbooks and learning manipulatives (i.e. educational toys) can be revised and adapted in order to prompt students to consider how historical narratives might have been presented differently if they were recorded through the lens of marginalized groups. There are great resources published that can serve as texts and curriculum guides, such as Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States of America and Amber Hickey and Ana Tuazon’s zine Decolonial Strategies for the Art History Classroom. Hickey and Tuazon (2019) also provide some essential tips for educators who are seeking to decolonize their curricula:

- Don’t just integrate material created by Indigenous peoples into your classroom; build trust and longstanding relationships with Indigenous artists and scholars.

- Share space. Invite Indigenous artists and scholars to speak with your class (and remember to pay them, even if it has to be out of your own pocket).

- You will be a better supporter of Indigenous peoples’ visual culture if you also support Indigenous peoples’ self-determination. For instance, donate to causes such as the Unist’ot’en Camp (http://unistoten.camp/support-us/).

- Consider providing students with guidelines regarding best practices in writing about Indigenous communities. Gregory Younging’s Elements of Indigenous Style: A Guide for Writing By and About Indigenous Peoples is a good reference.

- Visit archives and community spaces that may hold materials that are relevant in your process of creating a decolonial classroom space. For instance, the Interference Archive has many relevant materials.

If you are in upstate New York this summer you can see Frank Buffalo Hyde’s work in the solo exhibition Native Americana, on display through September 10, 2023 at the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse.

References, Notes, Suggested Reading:

Hickey, Amber and Tuazon, Ana. 2019. Decolonial Strategies for the Art History Classroom. http://arthistoryteachingresources.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Decolonial-Strategies-for-the-Art-History-Classroom-Zine.pdf

Newsome, Melba, “The Racist History of Mount Rushmore,” Reader’s Digest, 7 May 2021. https://www.rd.com/article/racist-history-of-mount-rushmore/

Reza, Musarrat Maisha, McEwan, Amy and Calvo-Hobbs, Times Higher Education, 6 July 22, https://www.timeshighereducation.com/campus/decolonising-your-learning-resources-representation-matters

Discover more from Artfully Learning

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.