As an art historian focusing my research on how art and pedagogy are integrated, I love coming across depictions of teachers in works of art. I previously wrote a post called “Portraying Pedagogy’s Progression,” presenting a condensed narrative of artistic representations of classrooms, teaching and learning; and describing what these works of art reveal about how social, cultural, economic and political ideologies shape the way pedagogy has been valued throughout time. In this post, which is part of a series of daily posts I am writing for Teacher Appreciation Week, I am showcasing art specifically centered on portrayals of educators from the past and present.

Raphael’s The School of Athens (1509-1511)

Raphael’s fresco adorning the walls of the Stanza della Segnatura (Room of the Segnatura) within the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace, is a paramount presentation of teachers from Ancient Greece. It is a great example of the contemporary zeitgeist explored and expressed throughout sixteenth century Italy, and some other parts of Europe. During this period, known as being the height of the Italian Renaissance, educators developed a curriculum that was inspired by Ancient Greek culture and humanism, notably Platonism, which is a term used for intellectual frameworks that are based on Plato’s philosophical teachings. Education for students during the Renaissance differed from prior Middle Ages pedagogy because it focused more on the lived experiences and natural phenomena than religious gospel. As a result, secular ideas like math, science, physical fitness and classical (i.e. Greek) philosophy, art and literature were key components of Renaissance teaching. The shift towards a human-centered perspective also meant that more attention was being given to addressing and contextualizing experiences impacting daily human life. Rather than largely focusing on living for the afterlife, the Renaissance brought attention to tangible and Earthly situations.

The impact of Raphael’s painting is twofold. It is a homage to classical intellectualism, as well as a representation of the major intellectual breakthroughs of Renaissance Italy. He symbolized this by depicting major academics from various eras of Ancient Greece, including Plato, Aristotle, Pythagoras, Ptolemy, Archimedes and Heraclitus; as well as his fellow Italian artists Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo who Raphael has introduced by merging their likenesses with that of Plato and Heraclitus respectively (see: Larsen, 2021 and Heyd, 2018). Furthermore, the painting’s aesthetics are exemplary of the advances in art education during the Italian Renaissance, most notably linear perspective which enables the painting to be interpreted in a realistic manner.

Winslow Homer’s The Red School House (1873)

The Red School House is one of several school related paintings that Winslow Homer made during the years between 1871 and 1874. Although the painting’s title refers to the architectural structure of a small one-room, rural schoolhouse seen in the background, the main focus of the composition is on the young teacher who stands contemplative along a dirt path in the foreground. These types of schools were common throughout the nineteenth century, often with a conglomerate of students, typically from first through eighth grade, and all taught by one teacher (see: Mydland, 2011).

Homer’s depictions of schools reflect a late nineteenth century nostalgic zeitgeist for representing a simple and harmonious lifestyle, which was an optimistic reaction set against the turmoil and disarray the country experienced in the aftermath of the United States Civil War. Children playing and learning, as well as young compassionate educators represented hope for the country to progress forward.

While Homer was working on his school themed paintings, the one-room schoolhouse was starting to be phased out for larger buildings and more age specific and developmentally focused curricula. However, there are aspects of the one-room schoolhouse that still exist within progressive educational practices, such as the communal ambience and cooperation between teachers, students and the environment. Children performed tasks in order to help their teacher maintain a functioning and organized classroom decorum, such as cleaning and providing general upkeep of the schoolhouse. Older students also offered pedagogical support by helping the younger students with their coursework (see: Kuhns, 2004). This type of scenario is a key principle of modern educational approaches like the Montessori and Reggio Emilia methods. In Montessori schools, young students are introduced to a range of playful, artistic and utilitarian objects including brooms, dining sets and dressing frames to help them practice independence and gain confidence while performing both creative and quotidian tasks. A similar learning atmosphere and philosophy exists within Reggio Emilia schools, which emphasizes founder Loris Malaguzzi’s philosophy that, “there are three teachers of children: adults, other children, and their physical environment.”

Winold Reiss’ portrait of Elise J. McDougald (1925)

German-American artist, Winold Reiss painted very soulful portraits during the heyday of the Harlem Renaissance. His work represents a variety of people who contributed to everyday life within the culturally Black neighborhood.

One of the distinct individuals he painted was Harlem educational reformer Elise J. McDougald who became the first African-American woman principal in New York City public schools during the early twentieth century, when she was temporarily appointed as principal of P.S. 24 in 1935. After graduating high school in 1903, McDougald earned her teaching certificate from the New York Training School for Teachers and completed coursework in pedagogy at Hunter College, Columbia University and New York City College. She received her first job as an elementary school educator in 1905 at P.S. 11 in lower Manhattan.

McDougald was a compassionate early childhood educator and administrator who also worked towards achieving social reform initiatives both within New York City’s school system and her Harlem neighborhood. She was a supporter of developing egalitarian educational experiences by focusing on a multidisciplinary student-centered curricula and combining Deweyian and Reggio Emilia frameworks like experiential learning, self-directed and projects and a collaborative classroom culture that would support students’ understandings of democratic living. She was also a key figure within the Activity Program, which supported the implementation of an intercultural curriculum (see: Johnson, 2004).

McDougald’s intellectual, sensitive and powerful characteristics are clearly represented within the portrait that Reiss composed of McDougald. Her facial features are realistically rendered, while the rest of her body is abstracted through a simple contour line drawing. This juxtaposition accentuates her poised and critical gaze. We get the sense that McDougald is a strong and thoughtful individual via this stylistic treatment.

Yuki Ideguchi’s My Dearest Teacher Hokusai (2019)

Hokusai was one of the leading Japanese ukiyo-e artists of the Edo period. He expanded traditional woodblock printing in a manner that represented a fusion of styles and elements from Eastern and Western art. His iconic work inspired an array of artists such as Vincent Van Gogh, Claude Monet, Hayao Miyazaki and Yuki Ideguchi.

Ideguchi has painted several compositions showing that Hokusai’s influence has been instrumental to his development as an artist. In My Dearest Teacher Hokusai Ideguchi paints a grayscale portrait of Hokusai amidst a colorful background that recalls his signature color palette, figurative motifs and iconic works of art, like his 1831 woodblock print The Great Wave off Kanagawa.

Ideguchi’s homage is a good point to discuss Hokusai’s legacy as a mentor of other artists. Aside from becoming one of the most famous artists of his time, he was highly sought after as a teacher; although Hokusai did not seem to enjoy teaching, and was loath to incorporate progressive pedagogical ideas and methods. Ukiyo-e researcher Iijima Kyoshin states in his 1893 Biography of Hokusai that: “Old Man Hokusai had many students, but he himself did not like teaching. If someone wanted to be his student, Hokusai would get out model drawings, which he had created and had woodblock printed, and have the student draw one of them. Then he would point out the shortcomings in the drawing. That was all he did as a teacher, but his pupils included many who became acclaimed artists.”

Despite the lack of student-centered facilitation, many of Hokusai’s proteges became renowned artists. It is apparent that being in the presence of their teacher spurred them to explore and expand upon their own interpretations of his bold risk taking and symbolic expression. This is also evident in Ideguchi’s contemporary artwork, which was made 170 years after Hokusai’s death. Hokusai might not have enjoyed being a teacher, but his enduring influence on generations of artists is a testament to the importance of having exposure to art education.

Agata Craftlove/THEMM! & Gregory Sholette’s The Future of Pedagogy: Survival Is Not Enough (2020-2021)

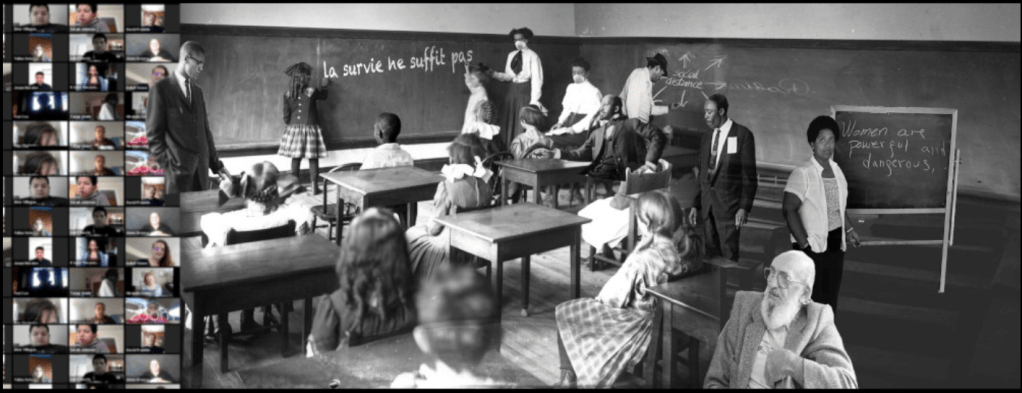

This artwork was made during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic through a virtual collaboration between Sholette and Craftlove. They note that it “co-envisions a post-Covid cyber-classroom hovering between the future, present and the past in which (left to right) Malcolm X, W.E.B. Du Bois, Paulo Freire, Joseph Beuys and Audre Lorde –all AI avatars designed by REU: Radical Educators Underground– gather to teach a student Zoombody by asking: what new, old or repurposed learning tools are necessary now for realizing a post-social pedagogical commons? We imagine a supra-individual agency capable of mutating successfully within the hybrid classroom. We say: swarm the future with the agency of the past! Survival is Not Enough!”

The Future of Pedagogy: Survival Is Not Enough encapsulates the ethos of social, emotional and intellectual liberation through its visual narrative. Each of the prominent figures depicted in the digital collage has offered profound insights into making classrooms and communities more just, equitable and egalitarian. Throughout the artwork the hegemonic barrier is dismantled. Although each of the notable historical individuals are powerful and formidable symbols of revolutionary social justice, they represent a non-hierarchical and collaborative means for teaching to empower. The students are some of the most engaged participants, which reflects the pedagogical philosophies of their educators. Standing in front of the chalkboard, a student writes “la survie né suffit pas” (“survival is not enough”). With the facilitation of their teachers they are actively learning to transcend what Malcolm X described as “a society that will crush people, and then penalize them for not being able to stand up under the weight.”

Malcolm X looms large in the front of the classroom, but despite his stature and historical clout, his presence is not overtly didactic. He appears contemplative and nurturing in this imagined scenario, reflective of his statement, “I believe in human rights for everyone, and none of us is qualified to judge each other and that none of us should therefore have that authority.”

Paulo Freire and W.E.B. Du Bois are both seated on the same level as the young students, exemplifying their status as observers, interlocutors and collaborators in the learning process. They each understood and expressed that they and their students were co-creators of knowledge and that they should learn from one another rather than through the traditional passage of knowledge from teacher to student.

Audre Lordre stands poised in front of a small moveable chalkboard where she has written one of her affirming statements, “Women are powerful and dangerous.”

Then there is Joseph Beuys, the artist and art educator who advocated for human beings to make beneficial contributions to society through art. He considered his students to be social sculptors and his art to be social sculpture. These identities apply to anyone who creates an artistic structure within a community that shows an awareness of social issues and supports a democratization of the artist-viewer relationship through collaboration and active discourse. This theory is intrinsically connected to the educational sphere because educators facilitate these kinds of experiences in their classrooms. In this artful composition, Beuys is writing one of his quintessential chalk diagrams on the board, but instead of “social sculpture,” he writes “social distancing,” a remark to the last two years of remote learning and disruptions to classroom communities as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

There are so many other great examples of teacher-centered art that I could have discussed in this post. The crux of the matter is that educators have had strong representation throughout the history of art, because their work is considered an essential part of the human experience. Artists clearly appreciate teachers.

References, Notes, Suggested Reading:

Frode S. Larsen. “Leonardo da Vinci in Raphael’s School of Athens,” Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, Volume 11 Issue 2 (July 2021), pps. 196-243. DOI: 10.5642/jhummath.202102.09. Available at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/vol11/iss2/9

Heyd, David. “Spoilers of the Party: Heraclitus and Diogenes in Raphael’s School of Athens,” Source: Notes in the History of Art, Volume 37, Number 3 (Spring 2018). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1086/698427

Johnson, Lauri. “A generation of women activists: African American female educators in Harlem, 1930-1950.” The Journal of African American History, vol. 89, no. 3, summer 2004, pp. 223+ https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A123755602/LitRC?u=anon~d00a2e41&sid=googleScholar&xid=1e78d19a

Kuhns, Roger. “School’s Out: The Past Times of One-Room School Houses,” Door County Pulse, 1 May 2004. https://doorcountypulse.com/schools-out/

Kyoshin, Iijima. 1893. Katsushika Hokusai den 葛飾北斎伝 (Biography of Katsushika Hokusai). Tokyo: Kobayashi Bunshichi (小林文七)

Mydland, Leidulf. “The legacy of one-room schoolhouses: A comparative study of the American Midwest and Norway”, European journal of American studies [Online], 6-1 | 2011, document 5. https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/9205

Discover more from Artfully Learning

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.