Education was not always accessible to the masses like it is today. We know from historical accounts that class, status and identity had a lot to do with who was able to study and partake in formal educational settings like primary schools and universities. Concerns about inequity and quality of life issues led to the implementation of public education, which became a global zeitgeist during the mid-nineteenth century. While public schooling dates back to ancient times, compulsory education laws starting in the early nineteenth century, ensured that students would be able to attend schools free of charge, from kindergarten through high school. Public school systems are by no means perfect, and we could spend a nearly infinite amount of time discussing how and why there still is a wide gap to fill with regards to ensuring that everyone has an equal and equitable educational experience (see: Chang and Mehta, 2020 and Gould, 2021). I have discussed these issues in prior posts (see: “Healing Our Glorious Wounds”, “Into the Weeds of Public Education” and “Want to Make Art and Education Great? Start with Community”), but for now, I would like to focus on the potential to utilize public education to address these very issues.

Making education a widespread possibility has changed the course of our world. The internet has further advanced how information is presented and obtained, especially the proliferation of open-access commons, such as Open Educational Resources Commons, known within the field of education as OER. OER is a public digital library of free educational resources from elementary to graduate level curricula that prompt teachers and students to utilize and expand the content following what is known as a 5R framework, which academic educators David Wiley and John Hilton III (2018) explains are the permission users are given to:

- Retain – the right to make, own, and control copies of the content (ex., download, duplicate, store and manage on a personal computer)

- Reuse – the right to use the content in a wide range of ways (ex. in a class, on a website, textbook or video lecture)

- Revise – the right to adapt, adjust, modify, or alter the content itself (ex., translate the content into another language or make modifications to suit the needs of different learners and populations)

- Remix – the right to combine the original or revised content with other material to create something new (ex., incorporate the content into a mashup)

- Redistribute – the right to share copies of the original content, your revision or your remixes with others (ex., give a copy of the content to a friend)

OER epitomizes the benefits of making information as readily available to the population at large in a democratic and socially engaged manner. The 5Rs are also intrinsic to how artistic thinking and activity transpires, and since this is an arts and art education themed blog, I am particularly focused on how the visual arts and design play a large part in shaping how we make learning more accessible and humanizing across the curriculum. One way of doing this is through the creation of visual essays that elaborate upon non-aesthetic themes and theories. Visual expression can turn abstract concepts such as formulas and code into tangible understandings.

Early eighteenth century English essayist and wordsmith Joseph Addison said, “what sculpture is to a block of marble, education is to a human soul.” The arts and education have gone hand-in-hand from the start. Art enables self-expression and existential interpretations of the natural world and constructed civilization, which means that it has enormous potential in forming our knowledge, feelings and social interactions. The artistic process supports cognitive development because it is an active and open-ended endeavor for acquiring knowledge and understanding through a combination of observation, experience and the senses. The idea that everything in life and the environment can be filtered through the lens of art, is the basis for social sculpture and social practice art (see: “Artfully Learning Audio Series, Episode 17: Social Sculpture” and “The Beuys and the Bees”), which is is a collaborative and often participatory mode of art making that involves people as the medium or material of the work.

Visual essays are a good alternative to academic writing because viewing images is a more commonplace activity and stimulating experience than trying to digest scholarly research. While data and research methods are essential to continue making advancements in certain fields, visual essays help to make discipline specific content more widely understandable. We all benefit when esoteric, yet transformative material and ideas are presented in lay terms. Art critic John Berger used visual essays in his formative book Ways of Seeing, to make the argument that seeing is not a neutral or passive activity but an active decision. This is the driving concept behind a journal called .able, which publishes visual essays on subjects that relate to art, engineering, mathematics and the applied sciences. The journal asks us to consider the enduring question of “how can we go beyond text in communicating these findings at the intersections of art, design, and science?” (quoted in Hyperallergic, 2023). The content in .able seems to espouse Berger’s ethos regarding how pictures can fuel our drive to attain knowledge both within and outside of our comfort zone and areas of expertise. Sociologists Yasmin Gunaratnam and Vikki Bell (2017) describe Berger’s use of text and imagery as helping to establish a paradigm for perceptual learning (i.e. to make sense of what we see, hear, feel, taste or smell), stating Berger “knew very well that writing has its limitations. By itself, writing cannot rebalance the inequities of the present or establish new ways of seeing.”

Typically, journal articles are created for academics and specialists in whatever field or fields the publication covers. .able seeks to change the readership of journals by adapting the formats and methodologies of traditional articles to suit and engage a broader audience. In doing so, the visual image plays a main role, and articles resemble artistic projects and interdisciplinary experiments just as much as they reflect academic discourses. .able is peer-reviewed, like most academic journals, ensuring that its content is rigorously presented and steeped in factual originality, validity and significance across the arts, applied science and social science fields.

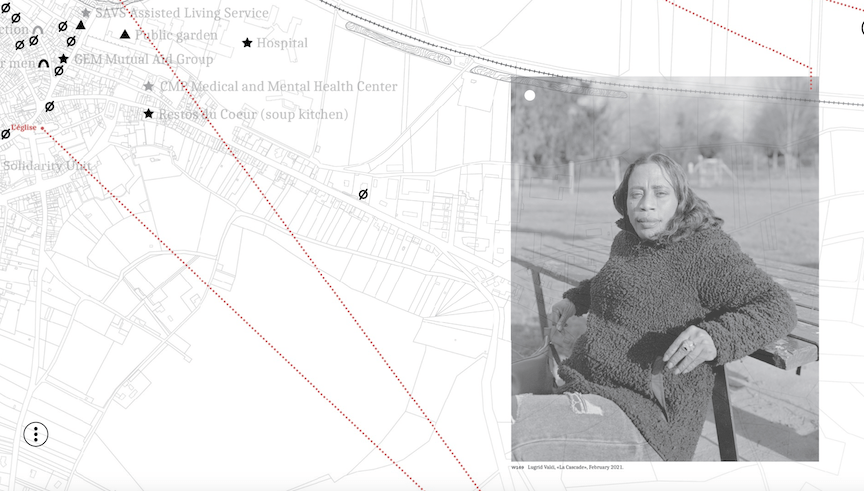

Visual essays in .able illustrate how photography provides a very human element that elicits an emotional response and more replete understanding of the complex issues and quantitative data being discussed in the article. An example is “Holding on: Photography and Reflexive Ethnography” by photographer Jean-Robert Dantou and researcher Florence Weber and graphic designer Ninon Bonzom. This project is a case study on migration to and from the French territory of Tonnerre, based on social, political and economic factors. The project’s objective is to elaborate on the following enduring questions: “What resources do people facing great difficulties linked to the increase in social inequalities between territories use daily? Why do some people in precarious situations move from one region to another and not others? How do these relocations, endured or chosen, contribute to locking them in or giving them back control over their lives?” (Dantou, Weber and Bonzom, 2023).

Photography and social sciences are infused together in the form of three visual layers through which a narrative unfurls that seeks to answer the aforementioned questions. Through an interactive platform on .able‘s website we can zoom in and out to study each of the sociocultural narrative’s distinct layers. Each layer is derived from the authors’ research and first-hand interactions with residents in Tonnerre. In layer one we are given a map of Tonnerre with pictograms distinguishing sites of significance, such as “the caring institutions that allow people to survive, the vacant places that play a key role in the arrival of precarious populations and the shelters that provide protection from the cold and rain” (Dantou, Weber and Bonzom, 2023). In the second layer, a selection of Dantou’s portraits are accompanied by captions giving us insight into how and why various individuals have settled in Tonnerre over the past decade. The authors’ note that this process was participatory and research based, explaining that each subject has “chosen the places where the pictures were taken. They have also chosen the places to which their portraits are linked on the map, either because they spend time there, or because they have in those locations an emotional connection, related to their hopes and doubts. And they have also coauthored the captions accompanying the photographs, to explain their singular relationship to the area” (Dantou, Weber and Bonzom, 2023). The third layer examines the intrinsic relationship between photography and its subject matter, environment and mechanics. Dantou, Weber and Bonzom (2023) note that, “from an epistemological perspective, this is about restoring the gap between the observed world and its photographic representation, a reminder that photographic materials, in order to be usable, must be related to the singular context of their production.”

The human element (i.e. how it makes us feel to see a person associated with demographic research) that is elicited from the photographs and other visual elements, is why the saying “a picture is worth a thousand words”is broadly acknowledged. Complex research that exposes the effects of conditions like migration or availability and access to resources, care and infrastructure, is well supplemented through the visualization of subject matter, which provides deeper understanding and empathetic responses. Art historians and OER educators Beth Harris and Steven Zucker (2012) explain that “this is because people want to understand art as they, and those around them, experience it—real, imperfect, and authentic. If we can bring these intimate experiences to people across the globe, why wouldn’t we?” This is evident in Dantou, Weber and Bonzom’s work, as well as other artful documentations of people, places and experiences in history painting, documentary photography and other visual art forms. The arts open hearts and minds, which helps to ensure that profound thoughts, ideas and narratives are accessed by a wide and diverse population.

References, Notes, Suggested Reading:

Bell, Viki and Gunaratnam, Yasmin. “How John Berger Changed Our Way of Seeing Art,” The Conversation, 5 January 2017. https://theconversation.com/how-john-berger-changed-our-way-of-seeing-art-70831

Berger, John. 1972. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin.

Chang, Ailsa and Mehta, Jonaki. “Why U.S. Schools Are Still Segregated — And One Idea To Help Change That.” NPR, 7 July 2020. https://www.npr.org/sections/live-updates-protests-for-racial-justice/2020/07/07/888469809/how-funding-model-preserves-racial-segregation-in-public-schools

Dantou, Jean-Robert, Florence Weber, and Ninon Bonzom. 2023. “Holding on: Photography and Reflexive Ethnography.” .able journal: https://able-journal.org/holding-on

Gould, Jessica. “New York’s Schools Are Still The Most Segregated In The Nation: Report,” Gothamist, 11 June 2021. https://gothamist.com/news/new-yorks-schools-are-still-the-most-segregated-in-the-nation-report

Harris, Beth and Zucker, Steven. “Museums and Open Education,” Smarthistory Blog, 6 October 2012. https://smarthistoryblog.org/2012/10/06/museums-and-open-education/

Wiley, David and Hilton III, John. “OER-Enabled Pedagogy.” International Review of Research on Distributed and Open Learning, 19(4) (2018). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/3336/

Discover more from Artfully Learning

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.